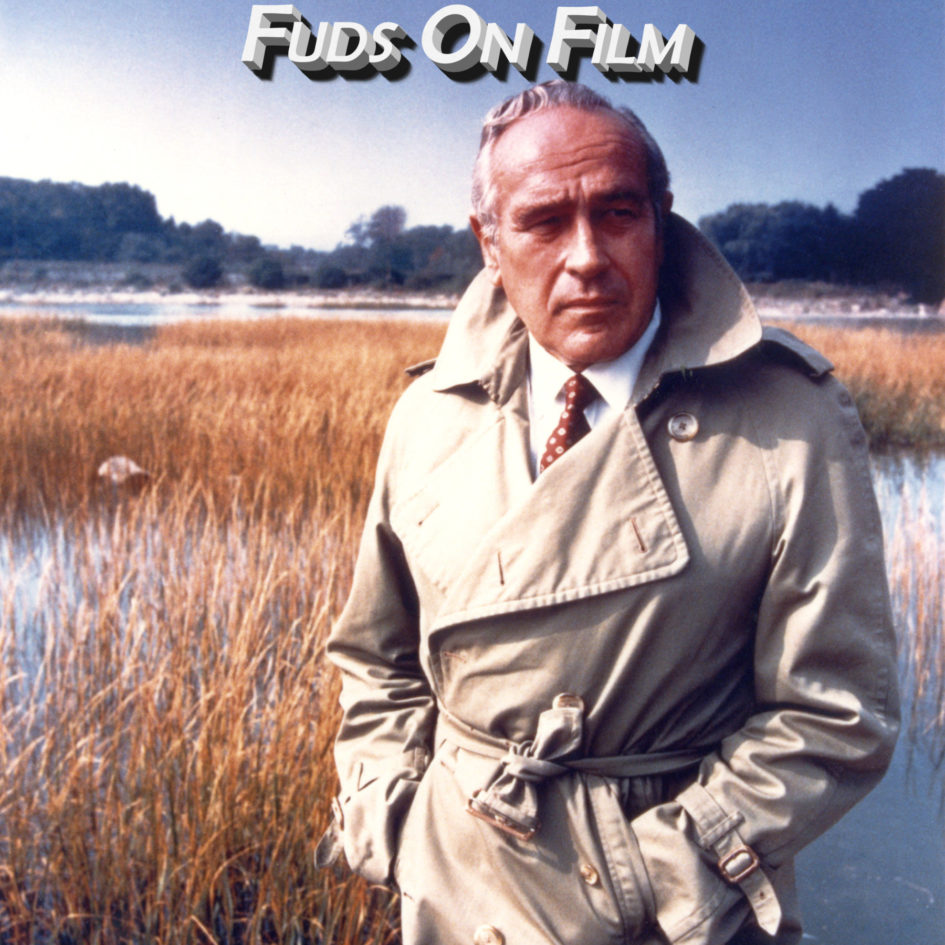

Robert Ludlum was a prolific author of primarily Cold War espionage thrillers, and so in a way it’s surprising that so few of his works made their way into cinema screens, and the vast bulk of those were part of the The Jason Bourne Imbroglio. In this episode, for no real reason other than a fondness for espionage bunkum and baroque titling, we are skipping over the various TV miniseries and taking a look at two earlier adaptations, 1983’s The Osterman Weekend and 1985’s The Holcroft Covenant, and we’ll start with that there Holcroft Covenant

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

Michael Caine plays New York architect Noel Holcroft, a simpleton, in this film written by simpletons, for simpletons. After an (entirely unnecessary) opening in the last days of the Second World War in Germany, in which we see three Nazi officers talk about a pact they are making for the benefit of their sons before all being shot by one of the group, Holcroft is contacted by Michael Lonsdale’s Swiss banker, Ernst Manfredi, who asks him to come to Geneva.

(Lonsdale’s character, I feel I should point out, works for “La Grande Banque de Genève”. Now, things do work differently in other languages – for example, “grand prix” may sound somewhat exotic in English but does, of course, mean simply “big prize” in French – but in this case I think “The Big Bank of Geneva” is a pretty good indicator as to the quality of writing on display here.)

Manfredi arranges to meet Holcroft on a ferry to deliver his important news, instead of inside the private, quiet and, above all, secure environs of a bank. ”You will understand once I tell you this information why we are not having this meeting at the bank”, Manfredi tells Holcroft. Now, call me a cynic if you must, but is it because it’s much harder to have people attempt to assassinate Holcroft immediately after your meeting? Anyway, immediately after their meeting, some people attempt to assassinate Holcroft. This is foiled by another assassin (this one currently not minded to assassinate Holcroft), though Holcroft himself is oblivious to this because, as I have already stated, Holcroft is a simpleton.

The reason for the meeting (and the assassination attempt) is that Holcroft’s father was one of the Nazi officers seen in the opening scene, who apparently had a change of heart, and channelled millions of Reichsmarks out of the Wehrmacht into a Swiss bank, so that reparations could be made to the Third Reich’s victims. This money, now in the amount of $4.5 billion, is to be dispensed at Holcroft’s direction, with the aid of the sons of the other two officers. Why this took the seemingly arbitrary time of 40 years to come into effect is not explained, but suddenly there’s a ticking clock on the whole thing, with some people determined Holcroft should sign the legal document to take control of the fund and some determined that he must not (though some of these seem to forget this later in the film). It also seems that this super-secret bank account is in fact known to pretty much everyone in the world with the exception of Holcroft.

So the film grinds along, with the ENTIRELY SHOCKING revelation that the fanatical Nazis hadn’t, in fact, had a change of heart, but wanted to create a new generation of fanatical Nazis, and that this money will enable this, by means of a ridiculous plan spelled out to the world’s media by a Holcroft who has, presumably, had the plot spelled out to him. Equally shocking is that almost all of the other people involved are EXACTLY what they seem, i.e., Nazis. Even, GASP!, the woman, who for some reason is called Helden, the German for “heroes”. (Maybe this is a name in other languages, but she’s German, so “Heroes” it is.) Only at two points was I wrong about any revelation, and that’s because I guessed Michael Lonsdale was in on it, and thought it might turn out that the Field Marshall was actually Noel’s father, who we don’t actually see die. Neither would’ve been out of place here.

Actually, I tell a lie. It was three, because I didn’t predict the incest subplot, because why the hell would I?!? It’s not written by a German, after all…

It is garbage, though, as opposed to The Osterman Weekend, it’s at least coherent garbage, though that’s cold comfort indeed. How much of that is the fault of screenwriters Edward Anhalt, George Axelrod or John Hopkins, or of director John Frankenheimer, I can’t say, though to be even-handed in my criticism, I suspect quite a bit, but my suspicion is that the greatest fault lies in the source novel, but having not read it I’m not in a position to confirm or disconfirm that suspicion.

Certainly, my notes – of which I made many while watching this – consist of lots of “whys”, and a considerable number of “fuck offs”. Oh, and not one single note was positive. I offer a select few now, in no particular order, as warning to you, and catharsis to me: (This review isn’t well written, but my excuse is that apparently it doesn’t need to be, as you can get a major motion picture made, directed by the director of possibly the best political thriller ever, even if you’re writing at the level of Dick and Jane.)

Why isn’t Noel more belligerent or questioning? It’s hard to know how we might act or react in many situations, but in many of the situations here I know damn well I wouldn’t be taking this so meekly.

On being expected to get on a horse: “You do ride, don’t you?” You can fuck off, can’t you?

An old man points a gun at Noel, who has done nothing wrong and is in this against his will. He wrests the gun from him, then doesn’t do anything. I wouldn’t use the gun, but you best be believing that if I had had that gun pointed at me the fucker who did it would now have a mouth full of teeth, wheelchair and age notwithstanding.

“I’m from MI5”. Well then, he must be. Why would he say it otherwise? Fuck off! Show me some ID. It may turn out to be counterfeit, but at least I’d have made a cursory attempt at confirmation.

“I love you” from ol’ Heroes McGee after knowing Noel for about two days. Seems cromulent. Oh, and fuck off, do.

“Don’t fly, the airport’s not safe. Drive, that’s better. But I’ll take the train.”

Noel eventually tumbles to the fact Heroes is also a rotter because she mentions a piece of information she could only have got from another conspirator. “I didn’t mention the dog”. Really? Really?!?! That? That ridiculous cliché?! Now, to be fair, sometimes that works. But in a film where it has been made abundantly clear that the character has been drilled for HER ENTIRE LIFE to be careful, use code words, to prepare weapons, to always be alert, to lie endlessly and convincingly, and that’s how she trips herself up? Kindly remove yourself from this place, and make love to yourself in a vigorous fashion.

What’s particularly irritating about this is that she actually was betrayed earlier, when it’s pointed out to Noel that his pistol, given to him and assembled by Helden, won’t actually function as the return spring is incorrectly fitted. This would have been quite a good way to do it, but, no, Noel is a 1W bulb at the best of times.

In the final scene, Noel hands a working pistol to Helden, and then turns his back on her and waits for her to kill herself. Lucky he’d read the script, I guess, because what if she hadn’t done that, Noel? You dim-witted pillock.

“Field Marshall, no wonder I was in love with you when I was a child.”

“You always were mad about uniforms.”

You’re the same damn age! Actually, the woman is older. What are you doing?

The main villain, Johann, is the son of a Nazi, who has been on the run his whole life, and used to live in South America. WAKE THE FUCK UP, MIKEY BOY!

And, finally you will be pleased to hear, a scene from near the beginning, in which a bewildered Noel gets into a car in which the barely-more-than-a-stranger at this point Helden is waiting for him, sitting for some reason in the passenger seat. Noel informs her that he can’t drive, to which she responds “Do you realise you’re endangering our lives because of your incompetence?” Get it up ye. Sideways. This last I extend to all involved with this piece of trash.

CIA agent Laurence Fassett (John Hurt) is heartbroken after his wife is killed by the KGB, as far as he knows, and throws himself into his work, uncovering a ring of Soviet spies, called Omega. CIA director Maxwell Danforth (Burt Lancaster) okays a scheme by Hurt to turn one, or all of them, while keeping schtum about the fact the Danforth actually ordered Fassett’s wife’s termination.

Back to the scheme. As simply arresting the three fingered Omega agents would tip off the KGB, Fassett intends to use the longstanding, university era friendship between them and the non-treason suspected firebrand investigative journalist, Rutger Hauer’s John Tanner to drive wedges between them and unravel the wider network. While Tanner cannot initially believe his buds were in fact budskis, seeing footage of meetings between suspicious characters and Dennis Hopper’s Richard Tremayne, a plastic surgeon, Chris Sarandon’s Joseph Cardone, a trader, and TV producer, Craig T. Nelson’s Bernard Osterman soon changes his mind, his only price being an interview with Maxwell Danforth when the dust settles.

The location for this scheme is one of their upcoming periodic weekend reunions, this time round at Tanner’s gaff, which Fassett stuffs to the gunwhales with surveillance equipment like it’s the house out of Night Trap. And, a side note, the alternative treatment of this material where the reunion occurs at Bernard Osterman’s residence, called Weekend at Bernie’s, is a radically different but more successful take on the subject matter.

At any rate, between some probing questions and subtle interjections of eyebrow raising prerecorded material, combined with some prior hints dropped by the CIA that someone’s on to them, it’s hoped that one or more of the compromised agents will confide in Tanner and try and find a way out. At least in terms of raising questions, tempers, and fists, this part of the plan seems to be going swimmingly.

And, well, at this point I have more than a few questions about the setup but was happy enough to go along with it, and I think it’s a setup with a lot of potential, however it’s very much a script that seeks to keep you invested by not so much pulling rugs out from under you, but the entire foundation of the story. And I suppose for the sake of good form I should give you some spoiler warnings, even for a near thirty year old film, but as I very much don’t recommend this film I don’t suppose it matters all that much. But you have been warned.

See, it turns out that Fassett had indeed figured out that Danforth is responsible for his wife’s death, and has concocted what has to be cinema’s most needlessly elaborate, resource intensive, obviously prone to failure, could not work in a billion years across a billion multiverses scheme to get revenge, I think, by forcing Tanner to expose Danforth by holding Tanner’s wife and kids hostage, which seems to have been something that Fassett could have simply done at any point by just giving Tanner an interview, which, turns out, he also does, so what the hell the point of any of the last ninety minutes of film is a complete mystery to me, and from having a poke around, also to audiences at the time, and also to the screenwriters, and the actors, and the director. At least I’m in good company.

Speaking of, this was controversial director / drunk Sam Peckinpah’s last film, and is by all accounts a fairy ignominious exit, albeit more of a continued ignominy rather than any sudden drop off. A shame, as a large part of my reason for wanting to watch this pair was to have a butcher’s at some of Sam Peckinpah’s work, as he’s another of these directors whose work I feel I ought to be more familiar with, but these lows do not have me yearning for any highs out there. It’s also overall a pretty solid cast, but one completely underserved by material that doesn’t give anyone any real characterisation to play with, although Hurt and to a degree Hauer pull things along with goodwill earned from other, better films.

There’s other avenues for criticism, like some overall flat direction and some surely dated at the time attitudes to gratuitous female (naturally) nudity, but the very massive problem of a plot that cannot stop making you ask, “But, Why?” every two-minutes past the half hour mark really doesn’t need any further examination. I suppose I should say, partly because of this baffling plotting I actually didn’t hate watching The Osterman Weekend, in a train-wreck sort of way, although I do not for one second recommend anyone seek it out.

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply