There are a number of notable film directors to have come from New York City, though some are particularly strongly associated with it, and with one borough in particular. Some of these filmmakers are short, bespectacled and often act in their own films. However, today we’re talking about one associated with Brooklyn, who isn’t a creep, and whose films we actually think are any good, so we know who that rules out.

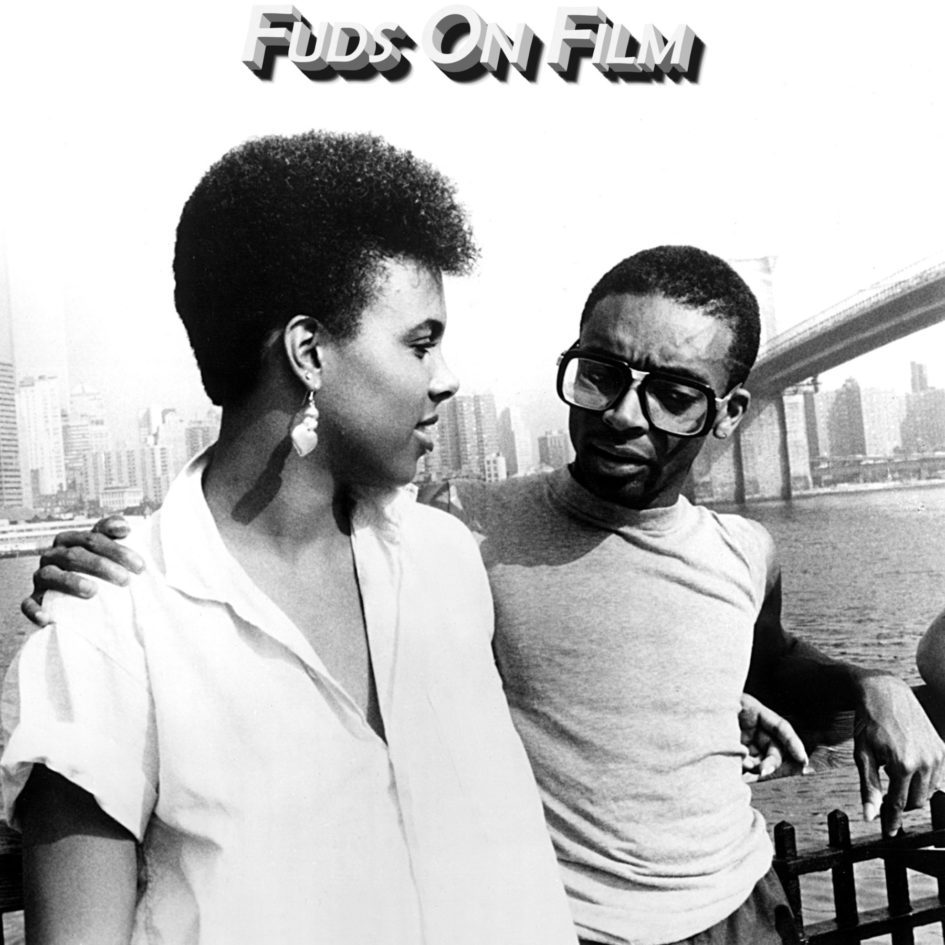

So, prompted by the recent release of Da 5 Bloods, we’ve decided to look at the work of Spike Lee for our main topic episode this month, though through a combination of an inability to suitably pare down a list and chronic procrastination, we’re spreading things out, declaring July 2020 “Spike Lee” month at Fuds on Film, and bringing you three episodes covering his work.

We’re beginning in this episode, in an entirely perverse way, at the beginning, from Lee’s directorial feature debut, She’s Gotta Have It, up to his 1995 crime drama, Clockers. One other film from this period, Jungle Fever, was covered in our Wesley Snipes episode last year, and it’s probably also worth mentioning we’ve also covered Lee’s Inside Man in a Compare and Contrast episode along with Dog Day Afternoon – both episodes well worth checking out, of course.

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

She’s Gotta Have It

Lee’s first full length feature sees us drop in on the life and relationships of Tracy Camilla Johns’ Nola Darling, a young Brooklynite who is juggling three men. Not, like literally. That would require a great deal of upper body strength.

No, she’s in simultaneous relationships with the seemingly upstanding Tommy Redmond Hicks’ Jamie Overstreet, the ludicrous male model John Canada Terrell’s Greer Childs, and Spike Lee’s Mars Blackmon, who I believe we’re supposed to find amusing. At least Nola does, so I suppose that’s the draw for her.

The three relationships have their ups and downs, with Nola not particularly committing to any of them, and it says here, enjoying the freedom that men have to cheat on their girlfriends. And, well, it is cheating, at least until it becomes clear to all parties involved that there are other parties involved, at which point the parties start to come to a close.

In terms of plot recap, perhaps surprisingly, there’s not a great deal more to it than that. It’s hanging its hat on a being a sex-positive story with a female lead, and, well, while that does qualify as something different – even today, to be honest, I’m not sure She’s Gotta Have It does the best job of explaining itself.

To be sure, it’s much more than a gender-flipped Alfie, but there’s not room in the script, or perhaps time and budget, to go much beyond the surface of things, either in characterisation of Nola’s blokes, who all came across as total tools, or Nola’s philosophy of her relationships.

When combined with a rape scene that’s so underplayed in terms of impact to all parties concerned you’d be forgiven for thinking it wasn’t a rape scene, there’s perhaps a good few reasons that Lee has chosen to recently re-explore these topics and themes, but in a (currently) 19 episode televisual format rather than a, what, eighty minute film once you take out Spike’s dad’s jazz stylings.

I’m in slightly odd place with She’s Gotta Have It. To be sure, it’s an assured debut feature and rightly place Lee on the “talent to watch” list, and while I’m already on board with the central message about the double standard on male and female promiscuity, as I’m sure are all the intelligent, discerning, open-minded and fresh-scented listeners of this podcast, I don’t think the film itself does a great job of explaining that message for the Neanderthal sections of the audience, who, to be fair, are never going to watch this anyway.

With a few ropey performances, I’ve more niggles with this film than perhaps any other we’ll talk about today, but broadly speaking I still rather enjoyed it and won’t dissuade anyone from catching up with it, but perhaps not the best place to start your explorations of his catalogue.

Do The Right Thing

Part of the purpose of this series of episodes is to determine our opinion on this, but it may be that Spike Lee’s greatest work is 1989’s Do the Right Thing, only his third feature.

Beginning as a slice of life of in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighbourhood, the heat wave being experienced in the city puts pressure on the residents, causing prejudices to come to the surface and racial fault lines to crack, with the film culminating in a black man being choked to death by a white police officer.

The film opens with Lee setting out his stall early, as Rosie Perez’s Tina dances vibrantly and sensually to Public Enemy’s iconic, anthemic Fight the Power, a song which was written for the film. Tina has a fractious relationship, and a son, with Mookie (Lee). Mookie lives with his sister, Jade (Joie Lee), and works as a pizza delivery guy for Danny Aiello’s Sal, who runs the local pizza joint with his sons Pino (John Turturro) and Vito (Richard Edson).

Other neighbourhood characters include “Da Mayor” (the wonderful Ossie Davis), Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith), a young man with a learning disability and a fascination with Malcolm X, Mookie’s incendiary b-boy friend, Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), Samuel L. Jackson’s DJ, Señor Love Daddy, and Bill Nunn’s Radio Raheem, recognisable from blocks away by the sound of Public Enemy blasting from his boombox.

The characters are, more or less, all memorable, and all have some part to play in either the events leading up to the finale, or in painting the texture of the neighbourhood: there’s no fat, nothing is unnecessary.

Most of the characters established, the main plot of the film begins to emerge. Pino, despite his favourite celebrities being black, as Mookie points out to him, is deeply racist, and resents that his father opened his pizzeria in a predominantly black neighbourhood. Meanwhile, Buggin’ Out questions Sal as to why there are no black faces amongst the restaurant’s “Wall of Fame”, only white Italian-Americans, and when he doesn’t receive a satisfactory answer, decides to organise a boycott of Sal’s.

This should be an empty gesture: Buggin’ Out comes across as an all mouth and no action kinda guy, and most people are inclined to ignore him. Only Radio Raheem will stand with him, and the tensions that have been rising during the day finally break when Sal demands Raheem turn off his boombox before serving him. Buggin’ Out begins the racial slurs, and surprisingly it’s Sal, not Pino, that returns them, belying his earlier statements, and starting a fight.

This leads to first a death, and then destruction, but despite an unlawful killing at the hands of the NYPD, the news story on the radio the next morning, tellingly, is about the mayor’s desire to investigate the property damage.

I watched Do the Right Thing for only the first time only a couple of years ago, and while I enjoyed it, I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of it, and mentally filed it under “yeah, pretty good”. I’ll have to have words with my past self, because on watching it again for this podcast, it’s so clearly something very, very special. It’s superbly made and written, with raw emotion, vitality, a superb cast playing wonderful characters, and a pretty decent chunk of humour, despite its themes and climax.

There is something almost stagey, or at least backlot-y, about the way Do the Right Thing looks, despite all being shot in Bed-Stuy, but I attribute that to the way DP Ernest Dickerson has captured the hot summer sun: everything is saturated and colourful, reflecting the personalities and passions of the film’s inhabitants, but heightened and slightly hyper-real, as if the insufferable heat has concentrated everything. Though it could also be the late 80s fashion: it wasn’t… um… subtle. Bright is very much the order of the day.

What else? The music is excellent, with a score by Bill Lee (Spike’s father) mixed with Public Enemy, and… well, it’s just excellent all round.

Mo’ Better Blues

In a way Mo’ Better Blues revisits the themes of She’s Gotta Have It, but from a male point of view, namely jazz trumpeter Bleek Gilliam, played by Denzel Washington. His jazz quintet are the star attractions at a nightclub, although Wesley Snipes’ Shadow Henderson is causing some friction with his grandstanding solos. The largely ineffectual band manager, Spike Lee’s Giant, advises Bleek to have a word, lest Shadow, well, I’m not sure what, mount a coup or something.

Bleek’s career is juggled with two women, not like literally. That would require a great deal of upper body strength. Joie Lee’s Indigo Downes and Cynda Williams’ Clarke Bentancourt may not know about each other, but they do know that Bleeks’ music is the only thing he’s truly committed to.

The break points in Bleek’s love life are perhaps obvious, but soon things are fracturing in his career too, with the rest of the band looking for their promised pay rise that Giant has not been able to secure from the club’s owners, Moe and Josh Flatbush, played by John and Nicholas Turturro. This can only accelerate Shadow’s designs on putting together his own band, perhaps with Clarke as a singer, but ultimately it’s the fallout from Giant’s gambling addiction that’s going to cause issues big enough for Bleek to radically change his outlook on life.

To a large degree this is a film about loyalty, whether that’s between Bleek and his old friend Giant, or between the band members, or the lack of it between Bleek and Indigo and Clarke, and the consequences of those bonds. It shares a little in common with other Lee joints in as much as it’s throwing a fair amount of thematic content at you, but unlike his next film Jungle Fever, discussed in podcasts passim, here it’s woven into the narrative in a more satisfying way.

Backed up with an almost impeccable series of acting performances – I think this is the last time Lee casts himself in a role of any significance, which is good, he can now afford better – there’s a lot to like in Mo’ Better Blues. It’s an easy watch with a great soundtrack, interesting characters and a solid narrative. Not peak Lee, but a very solid mid-league finish for the youngster who’ll surely be one to watch next season.

Malcolm X

I really don’t think there’s all that much that you can say about a biopic. Their structures tend to be similar, and they tend to suffer from the same problems of invention, imagination, excision and downright fabrication, differing only in degree.

The crucial factors, then, are to be found in subject and actor, and I can think of few more compelling combinations than the civil rights leader Malcolm X, portrayed by Denzel Washington.

Told in a linear fashion, with the occasional flashback, Lee’s Malcolm X covers most of the significant portions of the once-Malcolm Little’s adult life. Early on we see the beginning of his relationship with the white Sophia (Battlestar Galactica’s Kate Vernon), and his move from Boston to Harlem, where he becomes employed by Delroy Lindo’s gangster, West Indian Archie. Crossing Archie sees him flee back to Boston, where he starts a lucrative career as a burglar, until he is caught and sentenced harshly, less for the crime of breaking and entering and more for the crime of being a black man in a relationship with a white woman.

While in prison, he meets Baines (Albert Hall), an adherent of the Nation of Islam, who helps Malcolm through the withdrawal of his cocaine addiction and aids in his transition to being a Muslim. Leaving prison six years later, clean, learned in scripture and highly-politicised and passionate, Little travels to Chicago to meet the head of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, played here by Al Freeman, Jr., but for some reason voiced by Pete Postlethwaite in The Usual Suspects, which I, for one, found very odd.

Muhammad directs Malcolm to replace his original surname, Little, with the now famous “X”, and appoints him a preacher in the Nation of Islam. We then follow him as he becomes a popular, but controversial, figure in the Civil Rights Movement, through his hajj to Mecca, the re-evaluation of his beliefs regarding white people, his disillusionment with the Nation of Islam and, ultimately, to his assassination.

It’s difficult to argue that biopics have a great deal of value beyond entertainment, but Spike Lee’s Malcolm X may be one of the few that do, its more than three hours, which never bores, bringing humanity, depth and nuance to a man that is still vilified in some quarters today, portrayed as he is as an angry and violent man who urged death to the white man, ignorantly, or conveniently, ignoring his walking back of those views after his pilgrimage.

While it suffers from some of the ills of all biopics I began by talking about, Malcolm X still at least leaves a lot of the edgier statements in there, and is not afraid to show some of the man’s faults. The film is full of empathy, and attempts to understand its protagonist. While one might expect that Malcolm X would speak most to a black audience, it is absolutely not exclusionary: it’s an inspirational film in that it portrays a human, with human problems, who overcame them and changed his life. Key to that being successful is Denzel Washington, who is magnificent throughout: seldom showy, always utterly believable, whether full of righteous anger or oozing charm in a natty suit.

Talking of, the costume design is excellent, and Malcolm X is given some incredible ensembles to wear in the first act, though here I have one of my few issues with the film, though one I share with many period pieces: why is EVERYONE so amazingly dressed? Perhaps people simply cared more in the past, but it seems there should at least be someone who looks as ill-attired as, say, many of the characters to be found in our next film, Clockers.

Ernest Dickerson is the DP again, and he shoots the film in three distinct ways for each of the acts, with warmth and saturation for his early days in Boston and Harlem, and cold for Malcolm’s time in prison, visually marking the periods of his life. Apparently his skill doesn’t extend to talking Spike Lee out of using his “double-dolly”, though, as that makes another unwelcome appearance here, though that’s less nitpicking than my continued bafflement at its use: it resolutely does not convey what Spike Lee thinks it conveys, and feels completely out of place in the fleeting moment in which it is utilised here.

Like Do the Right Thing (and a number of other Lee works), Malcolm X was heralded on its release (a few months after the LA Riots which came in the wake of the acquittal of the police officers who beat Rodney King) as timely, a word I am weary of because it seems to have never not been the case, regardless of when you watch it. Timeless, then? Christ, let’s hope not. But good films are good films, regardless of time, and this is a very good film.

Clockers

Set in the projects of Brooklyn, we focus on the life of a street drug dealer, or “clocker”, Mekhi Phifer’s Ronald “Strike” Dunham, working for Delroy Lindo’s Rodney Little, the local kingpin. The main drama in the film kicks off when Little tasks Strike with the removal of another of Little’s goons, who Little believes to be stealing from him.

The homicide of said goon falls to Harvey Keitel’s Detective Rocco Klein and John Turturro’s Detective Larry Mazilli, although it would seem to be an easy one to clear up, what with Strike’s brother Victor confessing to having shot him in self defence. Rocco doesn’t buy it, though, suspecting he’s trying to take the fall for his brother, and sets about trying to prove it.

This has all proven too much for Strike, who’s now looking to exit the drug dealing game, and perhaps stop some of the kids mistakenly looking up to him as a role model, like Pee Wee Love’s Tyrone, following his life choices, although unsurprisingly Little is having none of that, especially when he starts to suspect that Strike may be coming to an arrangement with the cops to bust him.

The event that really causes all this to come to a head is perhaps best left for the viewer to discover, even if it does seem barely related to the actions and decisions of the main characters, and there’s also a little rope-a-dope concerning the narrative that Detective Rocco’s some up with in the later stages that’s a semi-effective twist, only undermined by the somewhat questionable character motivation required for it.

This is another Lee film where the setting, the characters and the politics of it are much more compelling than the narrative that they are living through, which is more of a problem in Clockers than the other films discussed today purely because it’s for once more focused on that narrative. And, it’s just not all that great. Not bad, to be sure, but not great.

Again, by no means an unenjoyable film, and one that has more than enough acting chops on display across a very talented cast to get by on, but it’s not essential viewing.

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply