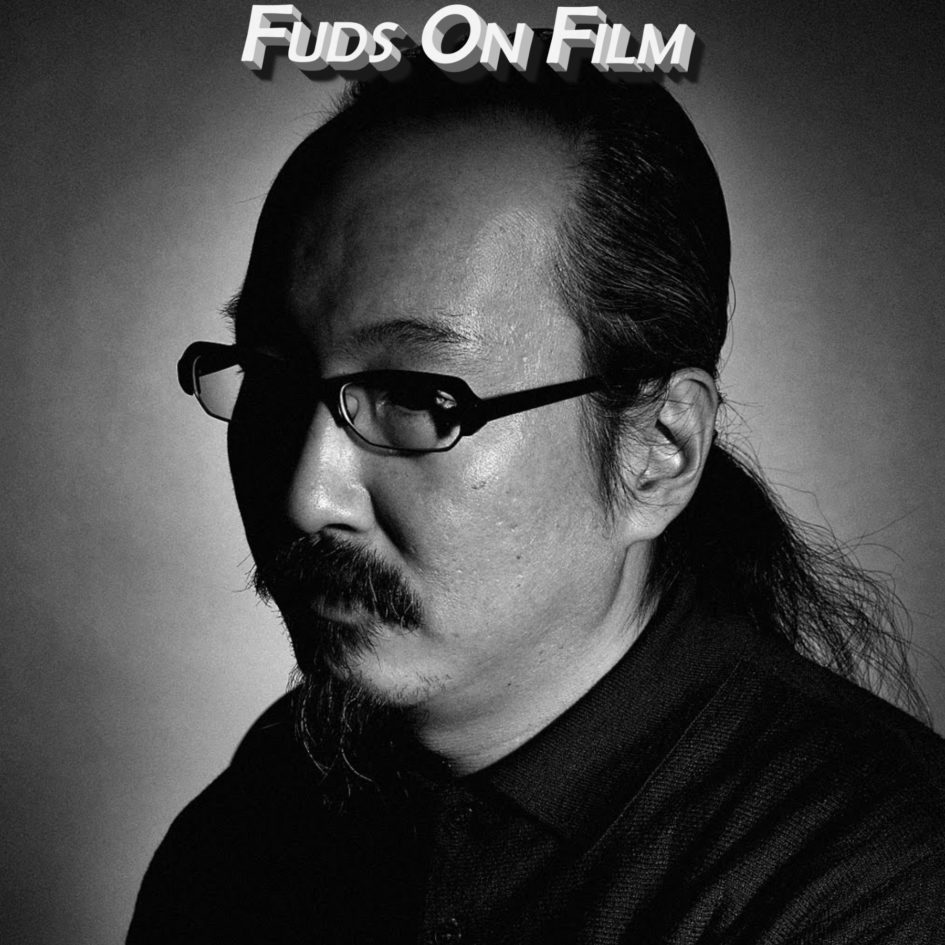

In this episode we’re going to be taking a look at the sadly sparse work of the Japanese animator, writer and director, Satoshi Kon, a favourite around these parts.

A native of Sapporo, Kon earned his spurs working under anime luminaries Mamoru Oshii and Katsuhiro Otomo, while writing manga and getting his first taste of directing with the original video animation, JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. However, it was with his first feature film, 1997’s fantasy and reality-blurring Perfect Blue, that he came to the world’s attention.

As well the blurring between fantasy and reality, Kon’s films are noted for female protagonists, themes of performance and identity, and a keen observation of both facial expression and physical bearing that is transmitted even through the relatively simple animation decreed by the constraints of the typically small budgets with which he worked.

Satoshi Kon’s films are, alas, also noted for being few, as the director was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in May 2010 and died just three months later, at the age of only 46, leaving behind him a canon of only four feature films. Those four, though, have influenced other filmmakers, perhaps most notably Darren Aronofksy and Christopher Nolan, and have left a lasting legacy.

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

Perfect Blue

When Mima Kirigoe quits a small time J-Pop Idol group to pursue a career in acting, it starts a chain of events that will cause more drama than is in the roles she’s offered. Struggling to make a name for herself, she agrees to a controversial rape scene with the hope of changing the public’s perception of her.

Some members of the public, however, seem violently opposed to any change in image, as members of the production crew start being gruesomely killed. This is upsetting enough, but between this stress and that caused by her being introduced to a website, “Mima’s Room”, pretending to be Mima’s diary and containing enough detail to know that this stalker has very close access to her, it’s a bad time for Mima’s mental health, and she will soon not know where the actor ends and she begins, or indeed where the person ends and her public image ends, be that new or old.

All this sets up a very engaging thriller indeed, albeit one that’s on repeat viewing, maybe a touch too well signposted and relying a little too heavily on a correlation between physical beauty and character, or rather the lack of both, which… well, maybe hasn’t aged well, but it was a bit of a crutch even back in ’97. That, however, is a slight niggle to pick with a story that’s otherwise a very tightly told 80 minutes of pleasingly twisty narrative and character work that’s never less than captivating.

I’ll always have a small truck load full of nostalgia for Perfect Blue, because I think it was the first anime I’d seen, certainly in a cinema, that deals with adult themes, or, well, adult themes other than assorted flavours of violence, so it certainly opened up to me a vista of other avenues of story that could be explored in the medium, more concerned with internal conflict than external. There had been things like Ghost in the Shell that I’d seen before it, I think, but that was a sci-fi robot trojan horse containing philosophy, not something, as with Perfect Blue that could feel as comfortable told in live action.

Well, at least thematically, however one of the advantages of the medium for this kind of thing is the recurring Kon techniques of merging competing narratives and realities to keep you guessing about what’s really happening, while not alienating the audience. I’ve seen less talented filmmakers try similar tricks and fall flat, but Kon was a master of it.

While I suppose you could say, almost objectively, that Kon went on to do better films on almost every axis you could judge a film, I would always have a soft spot for Perfect Blue for aforementioned nostalgia reasons so I was perhaps a little apprehensive about revisiting it, but I need not have worried. For a theatrical feature debut, it’s remarkably accomplished, polished, and absorbing. Spoilers – there’s not a Satoshi Kon film I’ve met that I won’t recommend, so arguing about positions in a league table seems a little redundant, particularly in a tragically small league. Might as well start at the beginning, and this is a very great beginning indeed.

Millennium Actress

Interviewer Genya Tachibana, documenting the closure of a now defunct movie studio, travels with his cameraman to the home of the reclusive actress, Chiyoko Fujiwara, the most prominent figure associated with the studio in its heyday, who mysteriously retired from acting and went into seclusion at the end of the 1960s while still a big star.

He has been granted an exceedingly rare, if not unique interview with the now elderly actress, occasioned by his returning to her a possession she thought lost: a small key, precious to Chiyoko, that opens “the most important thing there is”, given to her by a young painter and revolutionary during the second Sino-Japanese war, a man who had a profound effect on her life but whose name she never knew and whose face she now cannot remember. This is the stepping off point for Chiyoko’s recounting of her life and work to a rapt Genya.

In his previous film, Satoshi Kon explored what seems to have been something that captivated, if not obsessed him: the fluidity of objective vs subjective reality, and how the two overlap and even mix, particularly when art is involved. In Perfect Blue the protagonist’s stresses and doubts caused her reality to become infected by her work, with her role and its plot seeming to echo what was happening to her in the real world.

Something similar happens in Millennium Actress, but from the other side. Kon takes the idea that actors draw from their own life experience to inform a role and runs with it, with Chiyoko’s roles reflecting her own history, desires and choices as she chases the mysterious painter across time and place, from Japan to Manchuria, World War II to the Edo period and on through the Meiji Restoration and into a sci-fi future.

Each part of Chiyoko’s life, or roles, is told from the point of view of Genya and the cameraman, Kyoji, who, much to their surprise and consternation, find themselves not floating observers but near-participants in the onscreen action, having to dodge flaming timbers, arrows and other hazards. Genya, who it soon becomes clear is, and always has been, infatuated with Chiyoko, quickly becomes an actual participant, showing up time and again to aid Chiyoko’s character, reflecting something that happened in real life.

For me, Millennium Actress is Kon’s masterpiece: it’s inventive, touching, funny and emotional, and flows from one tone to another with ease. While Chiyoko’s pursuit of the painter is necessarily, and obviously, futile, the story never becomes maudlin nor, really tragic, even if it may seem like a tale of a life wasted as Chiyoko tends toward sanguine and philosophical rather than depressive and defeated.

Kon had polished his craft between Perfect Blue and this, with Millennium Actress displaying greater nuance and depth in its animation, and a bit more playfulness, too. Of particular note is the representation of Chiyoko, from the shy teenage schoolgirl meeting the painter and choosing to take her first film role, through to the elderly woman whose youth returns as she recounts her adventures. Aided by three different actresses voicing Chiyoko at different stages, Kon’s keenly observed animation portrays ageing through facial expression and physical bearing, allowing us to feel a genuine progression of an individual.

In the negative I have a handful of minor points, most of which seem to be the almost inescapable conventions of the genre: the cameraman is too broad and, frankly, cartoonish, for my tastes, though his reactions and comments do provide many of the film’s funniest moments, so it’s clearly not a character that I’m overly bothered by, and a few too many of Genya’s reactions are of that goofy, exaggerated type that bear little resemblance to anything an actual human would do. Other than that, I think Millennium Actress is superb, and I’d recommend it to almost anyone.

Tokyo Godfathers

Christmas is often stylised as a magical time of the year, and although ultimately that’s the case in the 2003 outing Tokyo Godfathers, the lead characters probably would not agree at the outset. Three homeless people have banded together into a loose, argumentative family unit, the teenage runaway Miyuki, gruff alcoholic and apparent victim of nominative determinism Gin, and maternal former drag queen Hana, whose stretched sense of togetherness is tested further when they find an abandoned newborn baby in the garbage on Christmas Eve.

While Gin’s looking to immediately go to the authorities, it seems Hana is looking on this as something of a miracle and wants to keep the child – after all, the previous parents clearly weren’t parenting correctly. This soon fades, and over the course of the Christmas holidays they seek to care for and ultimately reunite the kid with their family. The investigation itself will, however, uncover more about their own characters and pasts than that of the kid, often prompted by moments of such extreme coincidence that maybe thinking of it in terms of miracles is not completely unfounded.

I certainly don’t have anything negative to say about Tokyo Godfathers – the closest I can get to that is thinking that the final revelation about the true parents of the newborn makes for a bit of a last act dramabomb that ultimately I don’t think is needed, because the the primary reasons to enjoy the film, aside from the usual Kon table stakes of it simply being a beautiful thing visually and audibly, is the interplay between Miyuki, Gin and Hana, which is rarely less than delightful.

That said, Tokyo Godfathers is perhaps a more straightforward narrative than you’d have come to expect from Kon, at least inasmuch as while it does provide a few revelations and twists, they come through good ol’ fashioned character development rather than through smashing realities together and having surprises fall out. It’s not exactly Kon’s take on The Straight Story, but it’s at least a straighter story than his others.

As such, there’s probably an argument to be made that this is Kon’s least interesting work, at least narratively. However, there’s an equally valid counterargument to be made that the absence of world-bending frippery has allowed the characters the time and space to be a more rounded and well-realised ensemble than in any of this other films. I suppose you pays yer money and takes yer choice.

However, as mentioned previously, the only valid choice is to watch all of Kon’s films, as they, Tokyo Godfathers included, come with our seal of huge enjoyability. Well, figuratively speaking. We couldn’t get distribution for the actual seals. With its roster of colourful characters, in both personality and design sense, and a delight to spend ninety odd minutes with.

Paprika

In the near-future world of Paprika a new technology has been developed, dubbed the “DC Mini”. A device that can allow someone to see another’s dreams, it’s a little like a real-time version of Strange Days’ “SQUID”, though with a therapeutic, rather than law enforcement, intention. If it falls into the wrong hands, though, it could allow someone to invade another’s dreams, control them, and, eventually and somehow, allow the real world, and humanity, to be destroyed.

It falls into the wrong hands.

Beginning at the company where the DC Mini was developed, and with relatively small stakes at hand, like causing someone to throw themselves out of a window or off of a building, the scientists who created the device, Dr Atsuko Chiba and Dr Kōsaku Tokita, must track down the terrorist who stole the prototype devices, aided by police detective Toshimi Konakawa. They have another ally, too: Paprika, a feisty redhead with superhero abilities who guides patients through their dreams in therapy, and who may be Chiba-san’s avatar in the dream world, or may be a facet of a split personality, or may be a constructed, but entirely independent and real, person that just happens to live inside of Chiba-san’s head…

As events progress, the real world and the dream world begin to merge, and the great “parade o’ random mundane-yet-incredibly-sinister crap” that represents the dream, or possibly the psyche, of one of the initial suspects spills across into the subconscious of other people and eventually, via poorly-documented mechanisms, into the real, waking world, threatening existence itself.

People think dreams are great, and they’re not. Most probably they’re thinking of daydreams, which typically are great. Real dreams are often terrible, though: nonsensical, creepy, disturbing, unsettling… Paprika does a good job of conveying all of that, and that’s why I found watching Paprika a miserable experience. This is not something particular to this film: I generally, though not without exception, dislike dream sequences in films. They’re not enjoyable (this also extends to video games where dream sequences are also not uncommon, and there they’re pretty much universally terrible experiences, though often that’s a mechanical problem more than one of content – I’m looking at you, Max Payne).

I can read all of the imagery, I can parse all of the allusion and metaphor: I get it, I just don’t enjoy it, and since Paprika is almost all a trippy nightmare with tonnes of weird crap happening, I don’t like it. That’s something that disappoints me more than anything else, because it looks fantastic, belying its budget, it’s wonderfully colourful and inventive, and Susumu Hirasawa’s soundtrack is amazing, with the “Parade” track in particular being one of my favourite pieces of film music ever.

With all of that said, though, perhaps the most curious thing about Paprika is that one of the films on which it was particularly influential, Christopher Nolan’s Inception, is a film that I love. Brains are, like, weird, man.

Sadly, and unlike the rest of Satoshi Kon’s work, I simply cannot recommend Paprika, not least because, cruelly and without warning, the film opens with a clown: those miserable, painfully unfunny, tedious, negatively-entertaining nightmare things that exist solely to make the world less wondrous. Clowns are the worst, and I’m not having it.

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply