Back in 20th Century Spain there was this frightfully awful chap called General Franco who made everything jolly unpleasant, all things considered. After this Franco fellow popped his clogs in 1975 and democracy was restored to the country, there was a cultural and artistic flourishing throughout Spain, with much freedom of expression and a breaking of taboos often rigorously enforced under the Francoist regime.

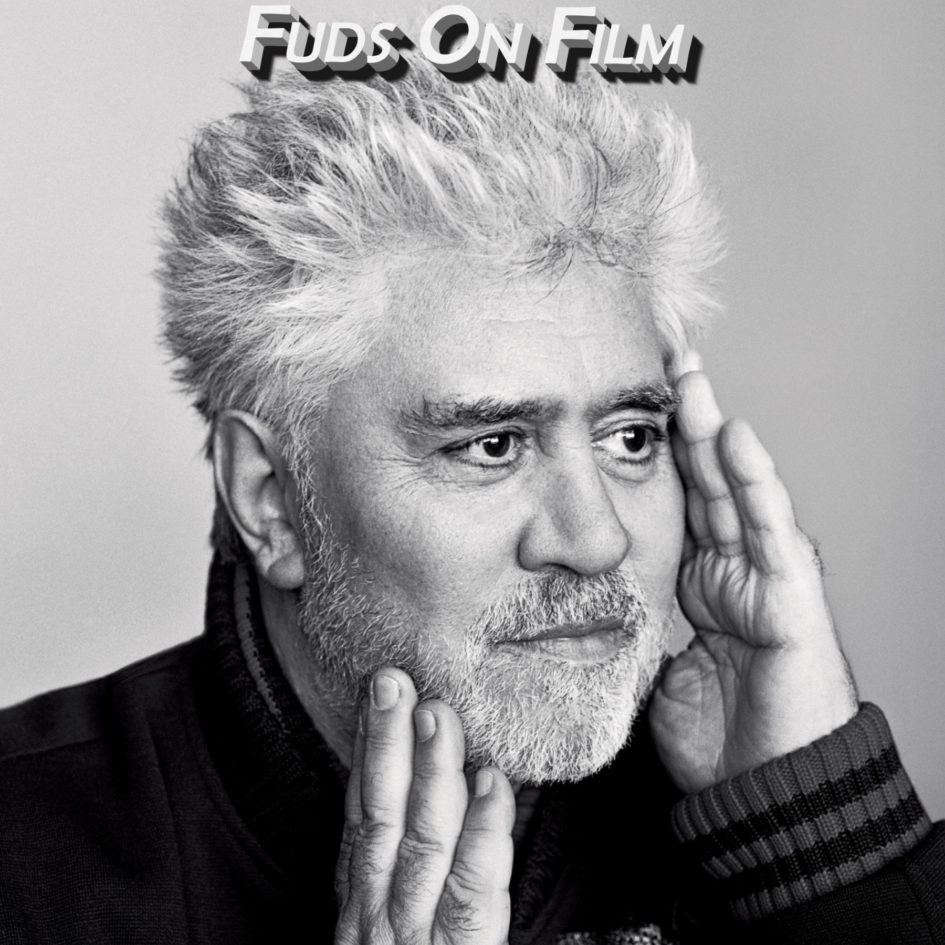

Perhaps the most notable of these cultural movements was in the capital, Madrid, and was known as La movida madrileña, or the “Madrid Scene”. One of the leading lights of La movida madrileña, and by far the most successful and influential in our particular area of interest, was Pedro Almodóvar.

In 1967, at the age of 18, Almodóvar moved to Madrid to become a filmmaker, which turned out to be pretty rotten timing as Franco (yes, him again) had just recently had the National School of Cinema closed. Having no other choice, young Pedro taught himself, and fortunately he seems to have been both wonderful teacher and attentive student.

Like many filmmakers he began working with Super-8, and also worked with theatrical group Los Goliardos, where he met Carmen Maura, who would go on to be one of his frequent stars. During this period he also wrote articles for magazines and newspapers, and even a novel, honing the writing skills that would see him go on to win numerous screenplay awards.

He took his early short films around Madrid and Barcelona, becoming well-known as, owing to the difficulty of adding sound to the Super-8 film, they were silent, requiring him to play music from a cassette and perform all dialogue and songs himself at the screenings.

Almodóvar’s films often feature female ensemble casts, LGBT characters, issues of sexuality, families and Catholicism, as well as being marked out by music, bold colours, kitsch and a reverence of cinema, while his work spans genres from darkly comic melodrama to film noir to farce, and sometimes all of these together.

Almodóvar is one of my favourite directors, and his name has been on our list of potential topics since almost the beginning of this endeavour, but thanks to my elite-level procrastination here we are, a smidge under four years later, finally ready to talk about him. Much of that procrastination (which some people apparently pronounce “laziness”) has been due simply to not knowing which films to cover, but I think in the seven titles we’ll be talking about today we can give you a good taste of Almodóvar and, hopefully, encourage you to check them out.

Well, I certainly do, having loved Almodóvar since I first saw one of his films, 2004’s La mala educación or Bad Education. But I know Scott had seen at least two films prior to that but was less than impressed, so I’m hoping he’s more appreciative of them on a revisit. We’ll get into that more as we go along, of course, but is there anything you’d like to mention before we start, amigo mío?

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

We could have begun, of course, with Almodóvar’s first feature-length film, the provocatively titled Folle… folle… fólleme Tim! (Fuck, Fuck, Fuck Me, Tim!), but…

Instead we’ve opted for another film also starring the director’s frequent collaborator Carmen Maura, 1988’s Mujeres al borde de un ataque de “nervios”, or Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, which seems to be broadly regarded as a good entry point into Almodóvar’s work.

Maura plays Pepa, a soap opera actress and voiceover artist, whose boyfriend and co-worker, Iván (Fernando Guillén), has just left her. That very same day Pepa has an appointment with the doctor that confirms that it isn’t just her that Iván is leaving behind, and she desperately tries to find him so that they can talk.

This leads her, after making a batch of either homicidal or suicidal gazpacho (use yet to be decided), to meet Iván’s ex-wife, Lucía (Julieta Serrano), and learn of his hitherto unbeknownst to her son, Carlos (Antonio Banderas). After unsuccessfully staking out Lucía’s flat all night in the hope of meeting with Iván, Pepa returns home to find multiple answer machine messages, though all from her model friend, Candela (María Barranco), and not from Iván.

Candela is hiding from the police because she’s been sleeping with a Shiite terrorist who has just committed an act of terrorism in Madrid, and she thinks the police will consider her an accomplice, and, like her name, isn’t the brightest thing in existence. Complicating things even further is the unexpected arrival of Carlos and his fiancée, Marisa (Rossy de Palma), who’ve come to view Pepa’s flat to sublet it.

Pepa must comfort her scared and suicidal friend, come to terms with Iván’s adult son, discover which woman Iván isn’t going on his trip with and which one he is, handle the murderous and psychotic jilted lover seemingly dropped in from the 1960s and find out why Iván left her. Oh, and let’s not forget the drugged soup or the police.

Women on the Verge… is indeed a fine entry point into the world of Almodóvar, being as it is a farcical screwball comedy with black humour and a strong undercurrent of melancholy and sadness played by a fantastic female ensemble cast, thereby presenting almost a microcosm of his work as a whole, or at least a pretty good slice through it. It is, to boot, also a thoroughly entertaining and very funny film on its own, and I think it’s reasonable to argue that if you don’t find something within it that clicks with you then Almodóvar may just not be for you. For that you will not have my condemnation, only my pity.

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!

Meet Ricky, played by a returning Antonio Banderas, a young man erroneously released from a mental institution. I say erroneously, as his only desire on release is to track down a porn actress he’d had a fling with on a previous escape and coerce her into loving him. He wisely kept that one from the shrinks.

Said porn star, Victoria Abril’s Marina Osorio is trying to go straight, working on a trashy but legit horror film and mostly kicking her drug habit, helped by her sister, Loles León’s Lola, the film’s assistant director.

In short order Ricky achieves his goal, atame-ing Marina in her holidaying neighbour’s apartment. Plans to make her love him are complicated by, well, apart from it being mental, Marina developing a chronic toothache that, thanks to her previous abuse, ibuprofen’s not making a dent in. So Ricky must try to find a suitable pain relief, which, a tense trip to the doctors aside, will leave him turning to the black market and uncovering one weird trick to allow Stockholm Syndrome to kick in.

Meanwhile, Lola has noticed her sister’s disappearance and is worried, but it seems be the sort of event that has some precedent. However, she’s also promised Marina’s neighbour that she’ll water his plants, so it seems there’s an inevitable horticultural clock on the discovery of Ricky’s scheme. However, it’s perhaps the events after the plan’s rumbled that’s the most remarkable thing about this film, and I suppose a spoiler warning klaxxon is required here, but Ricky’s plan has worked, it seems, and the three end the film living weirdly ever after.

According to the internet’s ultimate arbiter of truth, Wikipedia, this mash up of horror and romance is billed as a dark romantic comedy, which is very on brand for Almodovar. However, I find it very difficult to find a great deal of romance in this, and at least as far as the central strand of the narrative goes, much to find funny. Dark, yes, I think I can concede that.

There’s enough amusing oddness going on in the periphery to prevent my attention wandering too far, but I have to admit I cannot fathom the mental states of the agonists both ant and prot and that’s a huge roadblock for me with this film. By the end of it, it all just seems a bit stupid, and a waste of any investment I had in the characters.

On a technical level, and I suspect we should just take this as table stakes for Almodovar films otherwise we’ll repeat it constantly, it’s a very well acted and good looking piece of film-making. However the characterisation and narrative, for me, here just don’t tie together the way they need to, and so while I don’t regret watching this I can’t bring myself to recommend anyone else do so.

Live Flesh

We’re jumping forward almost a decade now, and moving from a sort-of romantic sort-of comedy with thriller elements to a pure thriller. 1997’s Carne tremúla, or Live Flesh, is based on Ruth Rendell’s 1986 Gold Dagger-winning psychological thriller Live Flesh, and begins in Madrid of 1970 amidst a freedom-curtailing state of emergency. On board a bus in empty streets, young prostitute Isabel (Penélope Cruz) gives birth. She and her infant son, Víctor, briefly benefit from the mayor and municipal transport director vying for publicity and perceived munificence, and mother and son are awarded free lifetime travel aboard the city’s buses, promising Víctor “a life on wheels”, and foreshadowing a “gift” he will bestow on someone else.

20 years later we meet Víctor again (Liberto Rabal), now an angry and impetuous young man who is furious that the woman he had agreed to meet after quickie sex in a club toilet the week before has forgotten all about their date, and him. The woman, Helena (Francesco Neri), is a junkie, only interested in getting her next fix, and Víctor is able to gain access to her flat when he rings her bell and she thinks that he is her dealer. An already tense situation is complicated when Helena produces a gun, and after a shot is fired police officers Sancho (José Sancho) and David (Javier Bardem) arrive on the scene. Víctor holds the gun on Helena, and during the fracas David is shot, relegating him to a wheelchair.

A few years later and David, a star wheelchair basketball player, is now married to Helena, who is clean and spending her considerable inheritance on children’s charities. A resentful Víctor, who blames David for his ills, has just been released from prison, and he intends to use the small sum left to him by his mother to pursue and seduce Helena, and ruin her and David’s life.

His plans are complicated by his unexpected relationship with Clara (Ángela Molina), the wife of David’s former partner Sancho, and revelations of unrealised truths behind the events of the night of David’s fateful shooting.

Satisfying and successful as a taut and engaging revenge thriller, Live Flesh contains themes of love, loyalty, desire and obsession, and also explores sexuality and crippled masculinity, and in a refreshingly unsentimental way. It also presents an allegory for a late 1990s Spain still suffering from and dealing with the repression, oppression and violence of the Franco era, and the long recovery period needed to heal a nation.

Most appealingly it does all of this with some fantastic performances, most notably Javier Bardem and Italian Francesca Neri, and a raw, angry turn from Rabal as the older Víctor, not to mention the affecting, vulnerable and desperate portrayal of Clara by Ángela Molina, and despite its contents the film ends on a defiant, and defiantly upbeat, note, both for its characters and its country.

All About My Mother

Eloy Azorin’s Esteban wants to be a writer. Well, unfortunately for him, his destiny lies under the tyres of a passing motorvehicle as he chases after a car to get an autograph. Them’s the breaks. His heartbroken mother, Cecilia Roth’s Manuela quits her job and moves back to Barcelona, where she hopes to find her son’s father, in time revealed – very minor spoiler klaxxon – to be Toni Cantó’s Lola, now living as a transvestite and unaware of Esteban’s existence.

Side note – I am not 100% up to speed on how exactly gender identity and terminology has progressed since this film was made, and I’m also rather taking various summaries at their word when “transvestite” is used rather than “transexual” and I don’t think it’s ever mentioned explicitly enough to say one way or the other what the intent of the film is, and it’s so far not an area of the Spanish language the Duolingo owl has tried to teach me. So apologies if this is tripping any wokeness alarms, I’m working with what I got here. Also, I can’t get anywhere in talking about this film without spoilering the hell out of it, so be warned.

While trying to track Lola down Manuela meets, and over time becomes friends with a young nun, Penélope Cruz’s Rosa, who was about to take a dangerous missionary position, but it turns out a very different dangerous missionary position has left her pregnant, and HIV positive. Already having a strained relationship with her parents, Rosa moves in with Manuela, who cares for her.

This will mean giving up her job as personal assistant to Marisa Paredes’ Huma Rojo, the actress her son ill-advisedly ran into traffic for, and by extension Huma’s drug-addicted co-star and lover Candela Peña’s Nina Cruz, a job Manuela essentially accidentally stumbled into. In time this job will pass on to an old friend, transexual prostitute Antonia San Juan’s Agrado, who’s as close to a comic relief character as the film has.

And so it goes, in a film that starts with traumatic events and leads up to more traumatic events and revelations, giving poor Manuela little respite. Indeed, this film has a narrative that would give telenovela writers pause, a jumble of exceedingly remote possibilities and coincidences used to puppeteer these poor character’s emotions, heartstrings and events for our entertainment. It is a clear testament to all involved’s talents that it does not feel like a contrived bundle of melodrama, despite, arguably, that being all that it is – certainly if you’re going to isolate the narrative from the character, for some reason, you weirdo.

It’s probably important to recognise Cecilia Roth’s performance as exemplary, as it’s her around the film orbits exclusively. The satisfaction of the film comes from Manuela’s efforts to deal with the traumas the film throws at her, and so that’s why her characterisation is centre stage, to the point that the film gives us flourishes that would flunk it out of the boilerplate screenwriting mills. There are plenty of scenes and character interactions wildly unnecessary to driving the narrative forward, but quite necessary for the character building.

I found a passing mention to me not liking this film greatly in a, what fifteen-ish year old review of Bad Education. In truth, I can’t now remember a damned thing about what I though of it (or Bad Education for that matter) at the time of first viewing, so perhaps it’s a change in tastes, or more familiarity with Almodovar’s rhythms, but I certainly like this a lot more now. We’ll go on to discuss one film in this podcast that edges this out as his finest hour for me, but it’s damned close.

Talk To Her

During a dance recital in a theatre a man is moved to tears. This expression of emotion makes an impact on the stranger seated next to him, something that will linger in his memory until they meet in the most uncommon of circumstances a few months later.

The crying man is Marco (Dario Grandinetti), an Argentinian travel writer. His attempts to write a profile for the newspaper El País of Lydia González (Rosario Flores), the most famous female matador in Spain, end in failure for the article but in unexpected success romantically. However, when Lydia is severely gored by a bull half a year later Marco finds himself alone again, sitting watch over her comatose body in a Madrid clinic.

Here he encounters Benigno (Javier Cámara), a nurse charged with caring for another young woman in a coma, the former ballet student Alicia (Leonor Watling). Benigno was the man sitting next to Marco at the recital, though Marco was unaware of him at the time. Marco confesses himself unsure of what to do about Lydia, but Benigno advises him, simply, to talk to her.

As the two men spend their time at the clinic they form a friendship, talking of travel and design; the joy and beauty of art; of women; of caring. Of obsession.

A revelation about Lydia causes Marco to leave and continue his work as a travel writer, and when he returns to Spain many months later further, shocking, revelations await him. Alicia has been raped while comatose and is now pregnant, and her most devoted carer, Benigno, is the main suspect, and it is in prison that Marco reencounters him.

While the abhorrent act at the heart of the film’s third act cannot be forgiven it can, perhaps, be explained, and at the very least it can prompt questions and even an understanding of the often hard to understand attitudes and behaviours of the friends and families of those accused or convicted of such heinous acts.

Almodóvar is, of course, an auteur, but Talk to Her is one of the films where this is most keenly observed. He draws strong performances, as per usual, from his stars but it’s his script and composition that have the most profound impacts in this work.

Hable con ella (Talk to Her) is calmer and less showy than many of Almodóvar’s other works, but retains many of his signature traits, including theatricality and questions of identity and sexuality. As usual, he treats his subjects with compassion and warmth, and while, perhaps, he gives his characters enough rope with which to hang themselves, refuses to be their judge or executioner. That’s a nifty trick to even attempt, let alone pull off, in a film that deals with the subject matters that Talk to Her does.

He questions gender roles, and in particular the idea that nursing of others (the act, not the job, but that too), tears and emotion, even devotion, are feminine things.

Music and eroticism have their place, too, including a largely dialogue free sequence in which Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso sings in a desert night, and a charged, lingering, sensual scene in which Lydia dons her matador garb, warrior like; a ceremony that echoes priests dressing before mass that has been seen in other Almodóvar works.

There’s even a seven minute “classic” silent film included, featuring Paz Vega, that may feel to some like it doesn’t belong but that is pure Almodóvar and that serves the purpose of potentially explaining how Benigno, if he is guilty, views his crime.

Bad Education

Note to self – stop giving myself the meta-textually heavy films to recap, as they are a pain in the ass.

Anyway, on the first level, we are introduced to Fele Martínez’s Enrique Goded, a director struggling to find his next project. He is visited by a childhood friend, Gael García Bernal’s Ignacio, or Ángel Andrade, as he’d rather be called. He’s just finished writing a story, “The Visit”, based in part on their childhood experiences at the church run boarding school they attended and I’m sure you can see where this is heading.

Initially dismissive, Enrique starts to read the story and soon decides to adapt it, with sections of “The Visit” playing out either through Enrique’s reading or production of it, telling of Ignacio and Enrique’s childhood relationship and love, moving into Ignacio’s story as an adult, now of a drag artist and transgender woman called Zahara – also played by Bernal.

In this story Zahara has a chance encounter with Enrique that prompts her to confront the priest who molested her as a kid in an attempt to blackmail him for money for gender reassignment surgery.

Meanwhile, in what we call reality, Enrique has embarked on a physical relationship with Ignatio despite not truly recognising him as his childhood friend, for good reason as it turns out, as we head into the final straight where all sorts of revelations occur as the story and the truth are reconciled.

Right, that’s not 100% accurate, but it’ll do.

Apparently I was a little non-plussed by Bad Education fifteen years ago – I’m a little warmer to it on this first rewatch since, which might be a case of forewarned being forearmed.

The table stakes remain – it’s a very well acted and good looking piece of film-making, but it falls into a similar groove as Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! and Live Flesh for me, inasmuch as the narrative, while compelling, gives some character motivations that are, well, weird and not very explicable, which hurts my investment in them. In a way, it’s too clever for it’s own good – if the characters were more cookie-cutter I’ve be more focussed on the narrative.

That’s a perverse complaint, to be sure – the film would be better if it was worse – but I suppose that’s the downside of Almodovar being held to higher standards than McG.

So, hugely watchable and technically excellent, to be sure, and I certainly like this more than Atame or Live Flesh (although would I similarly like them more on rewatch?), and well worth watching even if you don’t find the semi-sorta-kinda-autobiographical element of it interesting as a movie fan, but I still don’t love it.

Volver

In Bad Education there is seen a movie poster for a fictional film called “La abuela fantasma” or “The Phantom Grandmother”, which was, in fact, the working title for this film.

Volver (which means to return or come back in Spanish, and was left untranslated for the English market) begins in a small village in mountainous La Mancha where Penélope Cruz’s Raimunda joins the other women of the village in tending to and cleaning the graves. Job done, she, her daughter, Paula (Yohana Cobo), and her sister, Soledad (Lola Dueñas) visit their elderly aunt Paula (Chus Lampreave). They are concerned for her wellbeing, as she is confused and infirm, but she seems well-fed. This they largely accept as being due to Aunt Paula’s kindly neighbour, Agustina (Blanca Portillo), who checks up on her daily.

Certainly they put little stock in the idea that she’s being visited by the ghost of Raimunda and Sole’s mother, who died in a fire four years earlier, despite what Paula says: the East wind is relentless in the mountains, and it’s well known that it drives the people mad.

Returning to Madrid, Raimunda finds her husband, Paco (Antonio de la Torre), drunk, now unemployed and, though she’s unaware of it, leering over teenage Paula. This soon becomes a much bigger issue as an unwelcome advance on Paula sees Paula in a state and Paco on the floor, with much of his blood on the outside.

Raimunda takes charge, and temporarily places Paco’s body in the freezer of her neighbour’s for sale restaurant, the safeguarding of which he has entrusted to her while he is in Barcelona. Life, with its customary inconvenient timing, the next day delivers another blow to Raimunda: her beloved Aunt Paula has died, yet she can’t leave to go the funeral because of the corpse.

Her sister Sole does return to the mountain village, though, and when she gets back to Madrid she finds something rather unexpected in her car: her mother, Irene (Carmen Maura). Yes, the dead one, that’s right. Irene has unfinished business: her daughters, though primarily Raimunda, but she swears Soledad to secrecy for now until the time is right, so hides out in Sole’s flat and pretends to be a Russian.

Irene and Soledad’s relationship was difficult, but when mother and daughter are finally reunited truths are told and families made whole.

Volver deals with some really weighty stuff, including parental abandonment, betrayal, illness and more, not to mention death, dying, not being alive anymore and lack of life, yet it is so light, vibrant, joyful and funny, without ever being flippant, suffering from tonal inconsistency or ever feeling like it is anything less than absolutely sincere.

José Luis Alcaine’s lush and vivid photography is complemented by a great score by Alberto Iglesias, and together they create a world in which I would happily spend yet more hours.

But the film belongs to Penélope Cruz, who has never been better and without whom it’s hard to imagine the film working even a quarter as well. She’s radiant, captivating, beautiful. Glamorous yet also down to earth. Above all she’s sensual; a mass of dark locks and unconscious sexiness whose perfume you can almost smell. Forty years earlier and she’d have been Sophia Loren. But she’s not here as an object of desire, though there are men (very much in the periphery in this film) who desire her: for now she has much more important things to tend to, and all that she has to give is for her family and her friends.

Pedro Almodóvar is often considered a women’s director, and it’s truer than ever in Volver. Cruz’s Raimunda is hard-working, generous of time and spirit, determined, resourceful and never self-pitying, and, like the other women of the film, quite, quite capable of getting by without “menfolk”. For Raimunda and her friends and family men are nuisance, threat, heartbreak. Or irrelevances. But it’s not an anti-man film: the whole point of Volver is that it’s simply not about them.

The women here, both as actor and character, are tremendous: real and engaging, believable, human, even if some of the things happening to them seem to come from the telenovelas that partly inspired the film.

As I mentioned, Penélope Cruz is the film’s centre but I’ll add some notes of praise for two others in particular: Carmen Maura, who fell out with the director during Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and only returned to his films here, is mischievous as Irene, and Lola Dueñas’s Sole displays so much melancholy and loneliness in her face alone she doesn’t even need to speak.

The bright colours of Volver’s palette, especially the red, signify passion, but for what? Many things. Everything, perhaps. But I think mostly life: for a film about death in so many ways, it really isn’t about that at all, nor any of the other bad things. It is about life, and love, and it is magnificent.

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply