Today we turn our attention to Paul Verhoeven, in particular his most famous, Hollywood era works, namely RoboCop, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Showgirls, Starship Troopers, Hollow Man. Are they worth blabbing about? Would you like to know more? Listen in, then.

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

It seems strange, for a man of my vintage and interests, to try to explain Robocop as if it’s a thing that is not a universal part of human experience. It’s like trying to explain how water is wet. It’s been part of the background radiation of my life for, well, not quite as long as I can remember, but close enough, and it’s almost unfathomable that it is not thus for us all.

However, I suppose time makes fools of us all, and maybe there’s some people who only know the not awful but certainly nowhere near as good remake of 2014. You poor bastards. Let me then give some potted recaps of the 1987 original.

Set in Detroit, in one of those 80’s near futures where we seemed to be a half hour away from crime gangs running rampant on the streets (see also Predator 2), the po-po are overwhelmed and the government does the only thing it could reasonably do – bring in a corporation to clean up the mess, with their ultimate aim being to demolish Detroit and build a shining city on the hill, with none of of them poors getting in the way of their fancy haircuts.

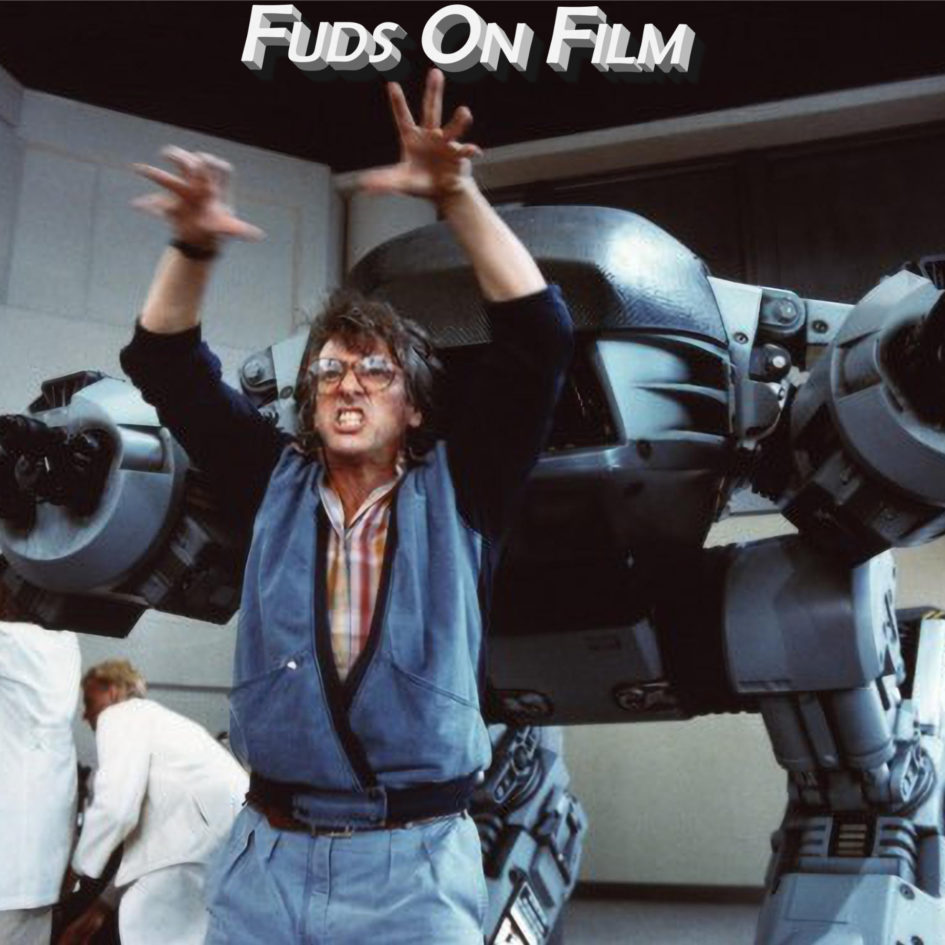

When Ronny Cox’s Dick Jones, a senior exec at Omni Consumer Products’ policing project, the semi-mobile gun platform Ed-209 goes quite spectacularly and messily wrong, Miguel Ferrer’s ambitious Bob Morton seizes the opportunity to get his robot cop project greenlit, earning him plaudits with his boss but Dick Jones’ enmity, and that’s a list Bob will soon find out it’s unwise to be on.

But, Robocop needs a head to drive the agreed upon total body prosthesis, which comes in the shape of Peter Weller’s Alex Murphy a cop recently killed by the rampant, mayhem causing Boddicker gang, run by, who else, Kurtwood Smith’s Clarence Boddicker, later revealed to be in cahoots with Dick Jones to further OCP’s schemes. How deliciously evil.

So, then, the soul of the film, I suppose, is about the mind-wiped Robocop’s mind slowly unwiping, and, with help from his old partner Nancy Allen’s Anne Lewis, getting revenge for the Alex Murphy he’s gradually reconstructing. Oh, and ludicrous levels of violence, often involving gruesome fates for Rob Bottin’s special effects creations. Poor Emil.

Wikipedia tells me “the effects were excessively violent because Verhoeven believed that made scenes funnier”, and whether Verhoeven actually believed that or not, it’s undeniably true. It might not necessarily be absolutely true that they don’t make action films like this these days, but they certainly don’t make anything like enough of them. It’s a very fun romp that never gets old. In fact, as corporations encroach ever more on all aspects of life, if anything it’s just getting closer and closer to becoming a reality. Yay, dystopia!

Recommended, one hundo percent.

Mr Verhoeven stuck with the science fiction genre for his next project, an adaptation of the Philip K. Dick short story, We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, a strong contender for the best adaptation of the writer’s work and a thoroughly bloody good romp in its own right.

The film stars, as you likely know, Arnold Schwarzenegger, as red planet-obsessed construction worker Douglas Quaid, who visits a company called “Rekall” in order to have a memory of a trip to Mars implanted in his mind, only to have this transaction expose him as an actual spy who has actually been to actual Mars. This results in many people actually trying to actually kill him, so he must get his ass to actual Mars and find out what the actual hell is actually happening.

On Mars, Quaid (who is, in actuality, Hauser, an agent of Martian administrator Vilos Cohaagen) meets with a band of rebels who believe the mysterious alien technology discovered inside one of Cohaagen’s mines (this technology being a McGuffinium-powered planet kettle) holds the key to Cohaagen’s overthrow and the freeing of the inhabitants of Mars from his tyranny. Or does it? This may all be happening inside Quaid’s mind, something a doctor from Rekall tries to convince him of.

Thirty years on, some of Total Recall’s effects look a bit ropey, though perhaps not as bad as you might expect, and the things that matter – the performances, the pacing, the plot, and, indeed, other things that don’t begin with “P” – all hold up very well. Verhoeven’s typical excess is here, and it fits, and there’s also humour throughout. Crucially, too, though neither could be considered the greatest of actors, both the protagonist and antagonist are charismatic and entertaining, with Schwarzenegger in particular giving a possible career-best performance.

Total Recall is, principally, an action film, and that’s a label it wears proudly and well. For a mainstream science-fiction film, though, but perhaps not surprisingly given its source, there is some depth in here in regards to notions of nature versus nurture, and questions of what constitutes reality. It is possible to have a discussion (which we perhaps will in a few moments) of whether or not the events within the film actually happened, or were all actually inside of Doug’s head as he suffered a mental collapse within the confines of Rekall. There’s plenty to suggest both throughout: both the alien planet kettle and Rachel Ticotin’s Melina look suspiciously like the images displayed to Quaid before his memory implant, but then he also dreamed about Melina before going there.

The “fade-to-white” at the end is film shorthand for waking from a dream, a number of characters throughout predict exactly how the plot will proceed, and there are non-diagetic musical cues related to the memory implant company, Rekall. None of which I buy, as it happens, as I am firmly in the “it all happened” camp, most principally because of the numerous scenes of characters whose actions and conversations the audience sees, but Quaid doesn’t and couldn’t. Oh, and also that the whole memory implant business doesn’t make a lick of sense, and would require time to be missing from a person’s life, and not one person in the entire world ever saying anything that contradicted the implanted memory, such as “you didn’t go to Mars, you were at work with me” etc, let alone the Quaid-specific “you’re not actually a spy”. But that breaks the entire film, so shhh, keep that one under your hat. Also, there’s nothing in this film that is as impossible to believe, nor as stupid, as a giant elevator that, for some reason, goes through the centre of the Earth. But that’s a thing from a film that doesn’t exist, so we can forget about that.

To return to the point at hand, the fact, though, that a) you could have such conversations about a blockbuster film like this and b) would actually want to, shows why Total Recall rightly continues to be regarded as one of the greatest science fiction films of all time, and why there was no need for a ludicrous, braindead, point-missing, hack-directed, piss-poor remake, so it’s good that nobody made one.

Another entry into my prestigious list of films that I’ve surely seen, that turns out that I actually haven’t, but have just seen it parodied so much back in the day that those parodies have become the film in my mind. With, I think perhaps a bit of accidental cross-filing of Fatal Attraction thrown in for good measure.

Basic Instinct is more of a return to the kind of films that brought Verhoeven to international attention, being, it says here, an erotic neo-noir. I’m not sure it qualifies on either count, but who am I to argue with Joe Eszterhas?

Michael Douglas’s San Francisco Detective Nick Curran is charged with investigating the death of a retired rock star, stabbed to death with an ice pick. Prime suspect is Boz’s bird, Sharon Stone’s Catherine Tramell, a novelist who’s last work featured murders with ice pick. Suspicious behaviour, or is Catherine being framed?

She’s not particularly forthcoming when questioned, well, with everything apart from the more delicate parts of her anatomy in that scene, but seeing as there’s nothing more than Nick’s hunch linking Catherine with the murder, she’s free to go.

Nick takes it on himself to obsess over bringing her down, an obsession that worries his girlfriend and psychologist Jeanne Tripplehorn’s Dr. Beth Garner, given that Nick is still trying to get back on the straight and narrow after accidentally shooting some tourists while high on cocaine.

He tries to get under Catherine’s skin, who responds in kind, claiming to be writing a new novel with Nick as a basis. When it seems that she’s got more details about his past misdemeanours than is publicly available, Nick blows up at the internal affairs cop that’s been on his case, suspecting him of leaking the information. He soon shows up dead, putting Nick in the frame.

And, well, so it goes, with messy details about both Nick and Catherine’s past being brought up and strewn around like dirty laundry, all during a torrid and frankly nonsensical affair, building to an equally nonsensical conclusion.

Look, I’m not disputing the fact that Joe Eszterhas scripts have made a lot of money over the years, I’m just arguing that whatever success they have found is in spite of the script, rather than because of it. That’s certainly the case here, as both Douglas and Stone, as well as the array of supporting roles, really go all out in selling their characters and in conjunction with this bombing along at a fair ol’ lick, it’s not an unenjoyable watch. It’s just one that as soon as its barrage stops, you be left with many more questions than answers, but fortunately, won’t care enough to bother about any of them.

Basic Instinct was, at best, a disposable potboiler back in 1992, and I think from the safety of today’s far flung future the only reason to go back to this would be to try and understand the cultural impact this had, although even in that regard, it’s only really that one scene that we’re talking about. By no means the weakest on today’s list, but not worth a lot of your time.

One of the interesting things about Verhoeven’s 1995 film, Showgirls, like Basic Instinct from a Joe Eszterhas script, is the cultural mindshare that it attained and, to a degree, still has. And… hmmm, just let me check… yes, that is the only interesting thing about it. This… story? I guess that’ll have to do. This story of a troubled young woman who heads to the world’s tawdriest city in order to chase a dream of being a dancer and finds, that shockingly, it’s not what she imagined, has become a cult classic, of sorts, and prompted such scintillating debate as, “is it so bad it’s good, or rather is it deliberately bad, or is it just unintentionally bad?”. The answer, of course, is “it’s irrelevant” since the salient point is that it’s bad. Very, very bad. So bad it’s nigh-on unwatchable.

And while the whole “so bad it’s good” thing might fly for the likes of Amir Shervan or David Prior, Paul Verhoeven is a real filmmaker who knows how to put a film together. It was derided at the time of its release as both bad and vulgar – the latter being something with which I have, like a bankrupt haulage firm, no truck, criticisms of vulgarity tending to carry with them intimations of a prudish and puritanical, not to mention hypocritical, mindset – but I find the appropriate words instead to be crass and cynical, while leaving some room for vapid. The whole film screams that it’s provocative for the sake of being provocative, and it has nothing of substance to say at all.

The troubled young woman is Saved by the Bell alumnus Elizabeth Berkley’s Nomi Malone, a spectacularly unlikeable, ungrateful and selfish moron, who is less a woman with a chip on her shoulder than a walking chip with shoulders, whom we meet hitch-hiking on the side of the road. Within moments of being picked up by a driver, she’s changing his radio and brandishing a knife at him. While the possession of a knife may be a sensible precaution, the scene is only the first of many in which Nomi shows a spectacular lack of gratitude for the help she is almost entirely dependent on for most of the film.

She soon arrives in Las Vegas, and looking, as she does throughout the film, every bit as gawdy and ugly as that city (“with the open-mouthed, vacant-eyed look of an inflatable party doll, Ms. Berkley should have been well suited to a film that treats its heroine like a shiny new toy”, as she was described by Janet Maslin of The New York Times), something which is itself perhaps some kind of attempt at a statement, as her make-up is notably different from any other woman in the film, and Berkley’s not an ugly woman.

In Las Vegas she’ll luck into a place to stay (but be ungrateful), luck into an audition for a popular dance show (and be extremely ungrateful), get used and abused by men around her (including Kyle MacLachlan with the hair of an absolute tit), and risk a fellow dancer’s life, and certainly endanger her livelihood, in order to get ahead. Her friend will also, for no additional value to the story that I can see, be brutally gang-raped in a house full of people, but have no police involvement, and in retaliation for which Nomi will beat up one of the men responsible (something, incidentally, seen in less detail than the rape) as if that is somehow commensurate with the crime.

Despite working as a lap and pole dancer at a strip club, Nomi will become shocked and upset at being asked to strip at her audition, an audition for an attraction that she knows is a topless dance show.

She will later become jealous about a man whom she physically assaulted, and yet who still bailed her out of jail, but that she otherwise doesn’t have a relationship with, in a scene that portrays her as impossibly dim, seeing the engagement ring on his fiancée’s finger but not, seemingly, understanding it until he himself tells her that they’re getting married, at which point she gets really sad.

And all of this will be accompanied by, to return to Janet Maslin again, whose review tickled me, “the soul-numbing stupidity that plagues Mr. Eszterhas’s dialogue”

The whole thing is a miserable experience, before ending in a stupid and highly improbable manner that presumably is meant to give some closure to Nomi, who clearly doesn’t deserve it.

The entire film feels like it’s some kind of great joke on Verhoeven’s part, but if it is, it’s not funny. Berkley’s acting is woefully, laughably bad, from her pathetic, regular flouncing temper tantrums that a toddler given to the dramatic might think were a bit much, to her orgasms by way of epileptic fit and, curiously for a character who is a dancer, her complete lack of ability at dancing.

We’ve seen in Total Recall that Verhoeven can get a good performance out of actors with limited range, and he certainly understands character and story, and that films should probably have them. So how did we end up with this?

You might argue over the effectiveness of it, but it’s usually possible to argue that Verhoeven’s excesses and provocations have a purpose, but that’s not so in Showgirls. It’s a button-pushing, boundary challenging exercise that seems to exist just to push buttons. It’s full (thought not as full as press and reputation might lead you to suspect) of nudity and sex, but it is perhaps the least erotic or titillating thing that I have ever seen (that is supposed to be erotic or titillating, I mean: I’m not comparing it to the beach assault in Saving Private Ryan or anything).

The last couple of years has seen two documentaries made about Showgirls, and an entirely baffling reappraisal of it as some sort of ahead of its time, proto-#MeToo piece, which is, frankly, fucking bananas (I remind you that this was written by Joe Eszterhas, writer of Basic Instinct and Sliver, whose general introspection and insight can be well-illustrated by his quote that, “I was a militant smoker, and in my case, I think I particularly used smoking because of what I felt was a kind of politically correct big brother assault on smoking”).

This is a stinking turd of a film, and isn’t even ironically enjoyable. Just say no.

It would be somewhere over twenty years ago when I Lost My Heart To Starship Troopers, crashin’ light in hyper space, Fighting for the federation hand-in-hand, we’ll conquer space, and we did speak about that love a couple of years or so back in our episode entitled Sci-Fascism, so I’ll try and minimise the recovering of old ground.

Verhoven here adapts and completely subverts Robert Heinlein’s novel of the same same, just as his casting subverts the meaning of the age of high school students. Casper “deffo not 18” Van Dien plays our protagonist here, one, Johnny Rico, a jock from a wealthy family who defies their will and signs up for military service, the only way to become a citizen with voting rights in this junta.

Not having much to offer intellectually, he’s assigned to mobile infantry, while his classmates, such as his girlfriend, Denise Richards’s Carmen Ibanez heads off to pilot school, Neil Patrick Harris’s slightly psychic Carl Jenkins heads off to military intelligence, and before long Dina Meyer’s besotted Dizzy Flores joins Johnny in the infantry as another leg to a love quadrangle, once Carmen is assigned to train alongside Patrick Muldoon’s Zander “Haircut One Hundred” Barcalow.

This soap opera stuff takes a back seat once war kicks off in earnest, a race of Arachnids, or Bugs, get all shirty when humans start encroaching on their space and commence hurling asteroids at us, including one that devastates Buenos Aires, killing Johnny’s family, and giving him the necessary motivation to get through boot camp after almost going home when a hilarious and fatal accident occurs under his watch on a training exercise. Medic!

The rest of it, you probably already have the gist of it – lots and lots of shooting of bugs, a mix of some early-ish CG that more or less holds up, well, better than a lot of the era, mainly because there’s enough practical effects and delightful models mixed in to keep the disbelief a little suspended, which alongside some impeccable production design makes this a delight to revisit.

Now, famously this had something of a frosty reception back on release, but has been reappraised over the years. We’ll get to that, but most of these reappraisals don’t tend to place a lot of focus on how much fun Starship Troopers is, and they really should. It’s a riot, with a great blend of over the top humour and action that’s more satisfying than any superhero film.

Said reappraisals are more about pointing out, apparently to the terminally stupid, that this is not, in fact, glorifying a fascist state and it’s lust for violence, but satirising this. I have long been unable to fathom how the former view ever came about, as this is very much a film where it’s irony is clearly visible from space with the naked eye. Of course a director who grew up in a country occupied by a fascist regime did not make a pro-fascist film. Dummies.

For a movie that is, on the face of it, stupid, it’s got a lot to say for itself. Mostly in ways that have become more obviously relevant over the past few years, sadly. The continuing march of the military industrial complex, the continual need for an enemy to justify that, the media manipulation that vilifies that enemy and “others” them, and all the other signposts on the way to a fascist state, and applies just as well inside the USA that it’s referencing, as seen with the militarised police response to BLM demonstrations and the like.

So, a deeply depressing film to put any thought into, but a wildly entertaining one on the surface of things. Highly recommended.

In Hollow Man, a loose adaptation of HG Wells’ science fiction classic, The Invisible Man, Kevin Bacon plays Sebastian Caine, an arrogant scientific genius leading a secret Pentagon research project to find a reversible method to turn people invisible, by the means of “phase-shifting a human being out of quantum sync with the visible universe”, which are certainly some words that screenwriter Andrew W. Marlowe put in the vicinity of one another.

Caine, your typical Porsche 911-driving rockstar scientist, the kind we’re all so familiar with, is, amongst his many negative traits, incredibly impatient, and when progress on his research isn’t quick enough, he accelerates human trials by injecting himself with his magic serum. He turns invisible (a process so thorough it can also make the food inside his body invisible, even when vomited out of it), but can’t turn back. At first this is a nuisance, because his invisible eyelids mean he can’t close his eyes to the light. (Of course, his retinas are also invisible, so he can’t see the light anyway, but science, as you may already be able to guess, is not Hollow Man’s strong suit, though that’s of little concern as it’s mostly a special effects showcase with some humans around the edges, with only lip service paid to anything else.)

In a short time, though, invisibility has caused psychosis, and Caine starts killing a bunch of people, most particularly the rest of the staff of his lab (poor Elisabeth Shue: her game performance here is far better than this nonsense deserves), because he’s now a god or something. Caine must be stopped. He is stopped. It’s not very edifying.

I worry about the personality and motivations of Paul Verhoeven at times, and Hollow Man does nothing to ease that. While preparing these notes, I came across this quote from the director:

“Hollow Man leads you by the hand and takes you with Sebastian into teasing behaviour, naughty behaviour and then really bad and ultimately evil behaviour. At what point do you abandon him? I’m thinking when he rapes the woman would probably be the moment that people decide, ‘This is not exactly my type of hero’, though I must say a lot of viewers follow him further than you would expect.” (And, yes, this is another Paul Verhoeven film featuring rape.)

Setting aside that at no point at all in the film does Sebastian Caine even approach “hero”, and that I disliked him within minutes due to his obviously being a colossal arsehole, pretty much the very first thing that he does on waking up as an invisible man is to sexually assault a woman. This is before the rape, but if you’re still on board with him after this I’d suggest you have problems.

H.G. Wells’ 1897 novel The Invisible Man is about a man who is trapped by his own hubris, and who has become insane and violent after spending too long unable to see himself. In Hollow Man, Sebastian Caine is a villain whose hubris gives him the means to fulfil the potential of the terrible and violent person that he clearly already was.

Wells was inspired by Plato’s Republic and the story of the Ring of Gyges, with Glaucon’s central notion, with which Socrates disagreed, being that “no man would keep his hands off what was not his own when he could safely take what he liked out of the market, or go into houses and lie with any one at his pleasure, or kill or release from prison whom he would, and in all respects be like a god among men”. That’s an interesting philosophical idea. Hollow Man is a boring and brainless slasher film in which a bad man becomes a worse man. Explorations of morality, and curiosity, happen in other films. But, hey, it had some impressive special effects!

I didn’t have the worst time with Hollow Man, but it feels pretty generic in many ways, and certainly, of the Paul Verhoeven films I’ve seen so far, it’s the one that felt most like he was simply a director for hire. Dismissive grunt out of ten.

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply