On September 30th, 1955, a Porsche crashed in Paso Robles, north of Los Angeles. The driver, a 24 year old man, was killed. Tragic, but not especially remarkable.

Yet numerous musicians, from Bonnie Tyler, Van Morrison and the Eagles to Taylor Swift, The Goo Goo Dolls and Scouting for Girls, have sung about that driver. Madonna talked about him being on the cover of a magazine, while Don McLean talked of Bob Dylan having borrowed a coat from him as he was lamenting the day the music died. Books have been written and films made about him, and uncountable others reference him, obliquely or directly.

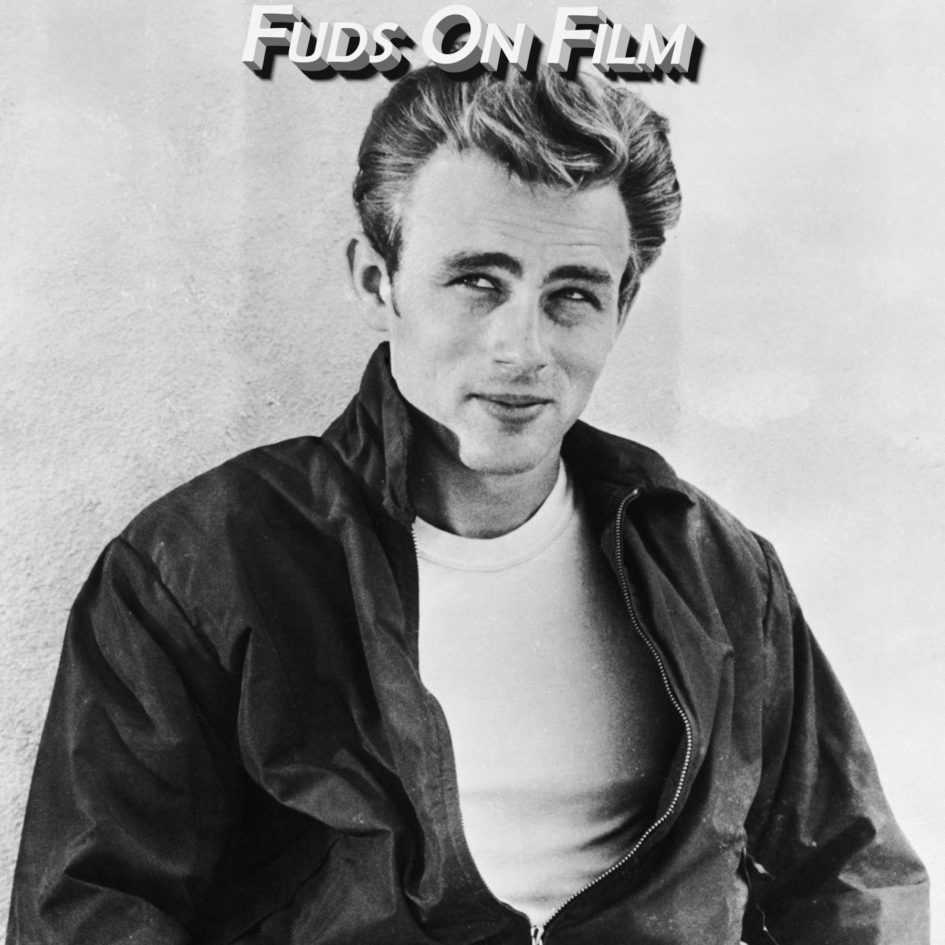

He was an actor with only three credited parts to his name, in films released between March 1955 and November 1956, yet he became one of the most iconic figures of the mid-20th century. That driver’s name was James Byron Dean, a name that has a lot of cachet even now. So much so, in fact, that in recent, ghoulish, news he is to be resurrected as some sort of unethical digital zombie in upcoming Vietnam War film Finding Jack.

For someone with such a scant body of work he cast a remarkable shadow for the half-century following his death, and I thought it would be quite interesting to look at the work of James Dean the actor, having only seen Rebel Without a Cause, and that many moons ago. I’ve wanted to explore Dean’s work for a while, and that recent news item made this quite a timely topic. So with that said, we now have to answer three questions: were those three films any good? Secondly, was Dean’s performance in those films good? And lastly, how ethical is the creation of a CGI puppet of a dead man?

Actually, we can skip that last one as obviously it’s exceptionally unethical and is not to be countenanced, so we can just move on to our usual fare, films.

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

East of Eden

John Steinbeck knew a thing or two about books. You may have heard of some his works. One of them, East of Eden, was his self-proclaimed masterwork; a 600-page behemoth chronicling the interwoven affairs of two families in California’s Salinas Valley around the run up to the First World War. Revered and lauded throughout the literary World, East of Eden would clearly be a great prize and career statement for the director talented enough to marshal its adaptation for the screen.

Three years after selling his buddies down the Suwanee in front of McCarthy’s House Committee on Un-American Activities, Elia Kazan was the man deemed fit for the job, and after screen testing the likes of Brando and Newman he settled on James Dean for the lead of Cal Trask, troubled son of Adam, a successful generational farmer, and brother of Aron, the young star of the family. The boys have grown up believing their mother to be dead, though we learn eventually that this is not the case.

Narrowing the source novel’s influence to its final third and set exclusively in the period immediately during World War One, the movie begins with Cal riding a train roof from Salinas through the mountains to the town of Monterrey, whereupon he stalks a middle-aged woman through the streets to a brothel and starts throwing stones at the building. The explanation for this is withheld at this point, and Cal returns home to harangue brother Aron and his fiancee Abra for a bit by acting like a general dick.

Meanwhile, dad Adam feels he and his sons have benefited greatly from the people of California, and in an attempt at giving something back he invests massively in the new technology of refrigeration, dreaming of a day he can ship fresh lettuce far and wide. Unfortunately, some railroad trouble means Adam takes a bath on that veg and subsequently the money invested in his equipment. Not to worry, as Cal decides the way to earn his father’s respect is to invest in growing beans, a commodity that will certainly skyrocket in value should America enter the war.

Cal’s relationship with his father, the emotional core of the movie, would best be described as tense, though on the evidence presented throughout the opening reels of the movie it is incredibly difficult not to agree with Adam’s perspective on his son, what with his every action being that of a petulant, emotionally retarded proto-Emo who displays a bizarre penchant for infantile histrionics, including pressing and rolling his face against various fixtures and fittings like a horny cat any time he talks to an adult. I might be missing something here, but if this brooding intensity I am baffled as to why the seven year-old me wasn’t fighting off hordes of adoring female fans.

Actually, I’m really confused by this movie; it does that thing America has been obsessed with in TV and film where actors in their twenties portray teenagers, only here Cal behaves like a pre-teen, but then we see them sitting in a bar drinking which, in post 1891 / pre-prohibition California, makes them at least 18. Steinbeck considered Dean here his greatest casting decision, and I can only imagine this kind of behaviour must have curried more favour or felt somehow more relatable in the 50s. From where I’m sitting in 2019 it’s baffling to think this is considered pivotal both as a movie and as a performance. I thought maybe I was taking crazy pills, what with the 10 star user reviews on various online movie resources, but I did at least find a couple of IMDB users as perplexed as myself. One of those described Dean as “rolling around like Gumby,” which meant I immediately had to Google “Gumby.” I’m pleased to say I enjoyed my five minutes of YouTube time with an anthropomorphised lump of plasticine infinitely more than two hours with James Dean.

I’m completely willing to concede that I’m wrong about all this, but my personal preference for Dean has very definitely been set by this first outing, and I have no desire for a second or third. I certainly don’t intend pointing my finger toward Steinbeck, because even in the heavily truncated story presented here there is bountiful narrative potential for an engaging arc. Certainly there is technical merit in Kazan’s direction, but nothing so much as to be considered a landmark, and having conducted some half-assed internet research I’m quite happy to let him take the lion’s share of the blame on account of what I view to be a great many bad creative decisions. Maybe my fellow Fuds fared better.

Rebel Without a Cause

Fresh from playing a 23 year old high school pupil in East of Eden, Dean got a chance to really stretch himself in his second feature, Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause, by playing a 23 year old high school pupil, but in the 1950s! Wow! Such different! So range! Many acting!

This film is Dean’s most famous, and provides the most iconic image of the man, in his red windbreaker, but we first meet Dean’s Jim Stark in a tuxedo, having left a shindig at his parents’ country club, got drunk and then got arrested, and awaiting interview in the “Naughty Youths” section of a Los Angeles police station. Also here are Natalie Wood’s and Sal Mineo’s actually high school-aged Judy and “Plato”.

Judy turns out to be a neighbour of Jim’s, and her talking to him on the way to school the next morning prompts her thuggish boyfriend to target Jim. Maybe. Really, it could be anything, as said thug, Buzz (Corey Allen) exists only to be a threat to Jim, and along with his friends has all of the depth of graphene. A character with actual depth turns out to be Plato, who actually has cause to rebel, having been abandoned by both his mother and father, and left in the care of the family’s maid (Marietta Canty). She clearly loves him but she’s not his family.

Lonely and bullied, Plato immediately becomes attracted to Jim, looking to him to be some combination of friend, lover and father, and they begin a friendship, though it may not last long as Buzz, apparently bored, starts a knife fight with Jim outside of the planetarium. When that ends prematurely (with a wonderfully brave security guard running away to get a very old man to deal with it), they agree to take part in chicken race. For some not entirely believable reason Buzz is unable to exit his car and ends up inside it. At the bottom of a cliff. On fire. Sic transit gloria Buzzy.

Jim is a troubled but not bad person, and wants to turn himself into the police for his part in the death, much to the horror of his considerably less moral parents. He doesn’t do so immediately, but his presence at the police station convinces Buzz’s friends that he’s turned them in, and they set out to deal with him, setting in motion a chain of events that will end in someone’s death.

While I really don’t get Dean’s enduring appeal, it’s good to know that there is something of substance there and that he actually had some talent, even if the accusations of aping Marlon Brando have some merit (though that’s more valid of a complaint in East of Eden than Rebel). As Jimmy Stark, Dean gives a sensitive portrayal of a young man tortured by demons he himself doesn’t understand and can’t identify, even if he’s given to mugging and overplaying it at times, though for my money it’s Sal Mineo as Plato that’s the stand-out actor.

No, the problems with Rebel Without a Cause lie with the story rather than the acting, though I still found it passable, but no more. It is an incredibly angsty film, and like the teenagers in its story, doesn’t seem to know quite what about. It is, in fact, a particularly well-named film. There is evidence of a collective societal handwringing at this whole new-fangled “teenager” phenomenon (“won’t someone please think of the children, WHO WE DON’T UNDERSTAND AND PROBABLY WANT TO KILL US”) and the never-out-of-fashion demonising of youth, though the film seems to point its finger at a failure of parenting – also seen in the discomfort of Judy’s father and his difficulty dealing with her becoming a woman (but to be fair, she’s super-creepy around him, though it may be mutual creepiness) – and decrying of the emasculation of the American Man.

But for me it’s the incredibly compressed time frame that’s the greatest problem. The events of the film take place over roughly 24 hours, and that’s barely enough time for all of the depicted events to occur, never mind the relationships that come out of them. While Judy falling in love with Jim is an order of magnitude more believable than Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson doing so in Giant, with their shared traumatic experience being mixed with at least a little of the chemistry there very conspicuously isn’t between Hudson and Taylor, it happens a matter of hours after Judy’s boyfriend was chargrilled in a stolen car. A little propriety, please.

Stewart Stern’s screenplay deals in some spectacularly sweeping generalisations: all teenagers are monsters, but it’s the fault of all parents, who are all useless, and every child would be much better off if the government was put in charge of their upbringing. It also manages to be a very Daily Mail-like film in its attitude to the yoots, yet also entirely antithetical to this in some of its sympathies.

Wait… so seeming to stand for one thing while also, at the same time, seeming to stand for another, diametrically-opposed thing? Wow, that really is like the Daily Mail. Though unlike the Daily Mail I found Rebel Without a Cause tolerable and with merit.

Not unenjoyable, but Rebel Without a Cause does not stand up in 2019, and while American society was very different in 1955, and therefore its resonance then may simply be lost to us now, that doesn’t explain the other 5 decades in between in which this, and Dean’s legend, persisted. I’ll apparently have to look elsewhere for the answers to my questions.

Giant

I have, unwittingly, given myself the longest of these films to recap, however as it’s the one I have the least interest in, I suppose that balances out.

Giant sees Rock Hudson’s Jordan “Bick” Benedict Jr., owner of a large Texan ranch make his way over to Maryland to look at a racist horse he’s considering purchasing. Sorry, race horse. It’s Bick who’s the racist. I apologise to horsekind everywhere. There he meets Elizabeth Taylor’s Leslie Lynnton, soon to become Lynnton-Benedict as they marry and return to Texas, and we follow what they’ll be getting up to over the next two generations.

Back at the ranch, genteel socialite Leslie initially struggles to fit in, butting heads with Bick’s sister, Mercedes McCambridge’s Luz, over, amongst other things, treating these damn useless layabout Mexicans as though they’re, y’know, human. A ranch-hand, James Dean’s Jett Rink, takes an immediate fancy to Leslie, which starts, or perhaps just reinforces a beef with Bick which is promoted to full on enmity when Luz dies, leaving Rink a small plot of land inside what Bick sees as his domain.

The years pass, with the Benedicts raising a son and two daughters, with the joys and heartache that can cause, while Rink strikes oil on his plot of land (this seemingly being one of those reservoirs located two inches under the topsoil) and becomes wildly successful, but still left harbouring feelings for Leslie, further escalating the Rink-Benedict rivalry, all coming to a head just after the Benedict grandchildren are born.

The only thing I appreciate about this film was the rare opportunity to use “back at the ranch” in a purely factual manner. That, actually, is a little unfair. I don’t have a great deal in the negative column for Giant, it’s just that I don’t have much in the positives column, either. Both Hudson’s and Dean’s characters I find difficult to wish anything more than ill for, both being racist wankbadgers, and/or drunks, and/or abusive, and, sure, flawed characters are the essence of drama, but there’s little to no redeeming characteristics or actions for either of them, or arguably in Bink’s case, at least until way too late, and as the balance of power between these two is one of the main pillars of the film, not giving a fraction of a crap about either of them rather undermines the whole point of the exercise.

Of course, they, and by extension Texan society, are clearly not being presented in a positive light by director George Stevens. That’s partly the point of Leslie’s character. But, well, an occasional reminder that “racists are bad” isn’t enough to excuse a three hour twenty minute epic largely being around characters that are reprehensible, but not in any interesting way, because the characters aren’t truly examined or interrogated in any depth. Or perhaps at all, really. The other pillar, the sort-of love triangle, also just doesn’t feel very believable, coming across more as a glorified schoolboy crush that might be headed somewhere when it tilts at a relationship between Rink and one of the Benedict daughters, but that’s far too late in the film, and brushed past too quickly to be of much interest.

Overall, this is just a bit dull. Not really my cup of tea in the first place, but I also find it strange that a film that’s so long, covering so much time, says so little about anything. It looks pretty enough, and I’ve no real issue with any of the acting or other mechanistic aspects of the film. It’s just the narrative, well, isn’t doing much of interest to me, with characters that aren’t of interest to me, hence my disinterest. How this became such a huge hit at the time is something of a mystery to me, even with the amount of star power behind it. No thank you out of ten.

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply