We turn our attention towards I’m Thinking of Ending Things, Bill and Ted Face the Music, Beastie Boys Story, Mulan, Ava, and Les Misérables in our latest episode. We’ve checked, and you are destined to listen in. Why fight it?

Download on Spreaker | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

I’m Thinking of Ending Things

Charlie Kaufman has, I suppose, long been the mass-market acceptable face of art-house nonsense, at least up until the confounding Synecdoche, New York cratered at the box-office, perhaps proving a touch beyond the upper limits of most people’s tolerance for art-house nonsense. Hell, as a more-often-than-not lover of art-house nonsense, it was beyond my tolerance. I’m sad to say that this was also very much the case for his latest, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, which will perhaps colour the lack of effort I’ll be putting into this review.

This is framed around a trip by a variably named young woman, played by Jessie Buckley, and her boyfriend, Jesse Plemons’s Jake, taking a car trip to meet Jesse’s parents, played by Toni Collette and David Thewlis. The drive is beset with some relatively meaningful conversations interspersed with the young woman’s occasional drifts into reverie, which from my addled memory perhaps sets up the themes that I think Kaufman hopes to explore in the next section, but I think I may be a little to kind to it here.

Said next section, the awkward visit to Jake’s parent’s farm, jumps around so much in time, character history and narrative that there’s really no point in me trying to explain any of it, and as far as I’m concerned, attempting to divine any meaning from. It’s very much Synecdoche, New York levels of confounding art-house nonsense, and I am very much not here for it.

Perhaps a little too close minded, and I can see if you’re looking at this more as a text to read and interpret you may get a good deal more out of this. Personally I think it’s asking a little too much of the audience to reconstruct quite so much of the meaning of, well, everything in the film, and I found myself entirely checked out by the ending of things.

There’s clearly lots of good work going on here, from the committed performances of the cast and all of the technical details, and the arbitrary dance number, but it’s all in service of something that’s, if not entirely impenetrable, at least more effort than I consider it is worth to penetrate. Oo-er, missus.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things is not, I suppose, in the technical sense of things, “A Bad Film”. It is, however, a film I roundly hated, and hope to never think of again. So, strong nonrecommend.

Bill and Ted Face the Music

I’ve been waiting since 1991 for that to make sense, and Bill & Ted Face the Music, the long-gestating sequel to Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey conspicuously fails to address this, so it can get bent. Zero stars.

Bill & Ted Face the Music finds our titular heroes, played by Alex Winter and Keanu Reeves, having thus far failed to write the song that will unite humanity and save the world, and Wyld Stallyns, rather than being the stadium-filling rock behemoths they ought to be, are a wedding band, destiny being quite the burden to put on people. But at least they have their families: the princesses (in their third different castings), Ted’s dad (Hal Landon Jr.), Missy (Amy Stoch), now married to Ted’s brother, and their daughters, Thea Preston (Samara Weaving) and Billie Logan (Brigette Lundy-Paine).

Our heroes’ failure to write the prophesied song, though, is about to catch up with them, as Rufus’s daughter arrives from the future to tell them that time and space are collapsing and that the universe will end in a couple of days if they don’t produce the goods. To this end, Bill and Ted decide to just hop through time to visit various different versions of themselves to find whichever version finally wrote the song, then snaffle it. Simple. Except for the totally-not-a-Terminator evil killer robot (Dennis) that’s chasing them, to fulfil the future Supreme Leader’s belief that it’s their death that will unite the world. Most non-non-heinous.

Meanwhile, Thea and Billie take a time trip themselves to help their dads, with the objective of forming the world’s most excellent supergroup.

Alex Winter and Keanu Reeves, along with writers Ed Solomon and Chris Matheson, have been at pains over the last decade to convey the message that this belated sequel is not simply a cash-grab, an attempt to capitalise on trends for 80s or 90s nostalgia, that they’re just friends who love each other, and the characters. And I believe them: the film, like the characters, is refreshingly free from cynicism. The characters have problems, but they all love each other, there’s no real conflict, at least beyond that which can be remedied by salving wounded pride, and they retain the harmless innocence of the two teenagers who travelled through time to find So-Crates, Beeth-Oven and Bob Genghis Khan. And that’s kinda nice (and not just in this epic shitshow of a year, but at any time).

Which is not to say that film is without problems, as it isn’t, and perhaps the most glaring one is Keanu Reeves, who, more than anything, seems to have forgotten how to play Ted. It’s like he just doesn’t quite have that character in him anymore, which is a pity. Much of that is made up for, though, by an extremely keen Alex Winter, who doesn’t even act nowadays, having been plying his trade behind the camera for much of the last three decades. Winter seems delighted to be revisiting his most famous on-screen role, and his enthusiasm is most excellent.

Face the Music suffers from being rather loose and unfocused, though that’s a criticism that can also be levelled at the previous two films, so it’s fitting. Once again the princesses could be omitted entirely without anyone even noticing, but their presence here does offer up a particularly entertaining marriage counselling sequence. Samara Weaving and Brigette Lundy-Paine as Bill and Ted Mk. II are great, and their subplot, while a rehash of Excellent Adventure is fun, and William Sadler’s return as The Grim Reaper is entertaining.

I would describe Bill & Ted Face the Music as “alright”, and definitely the least of the trilogy, but given how badly something like this could be messed up, I’ll take that as a victory, particularly when my time is respected with a completely appropriate 91 minute running time. Sometimes “nice” and “not awful” are good enough.

Beastie Boys Story

The Beastie Boys Story is, and let me pause for a minute to prepare you for the sort of galaxy-brain level insights that you come to this podcast for, is the story, right, of the Beastie Boys. It’s a filmed stage show where the surviving members of the band, Michael Diamond and Adam Horovitz, narrate a potted presentation of their life and career, from their early days, through initial success with Def-Jam as a frat-bro rock/rap parody of themselves, their regrets about becoming that mask, and their long road to reinvention and success on their own terms, a path that ended after the untimely death of Adam Yauch.

To a degree, I’m not sure there’s much need for more of a recap than that. MIke D and Ad-rock prove themselves to be engaging storytellers, and it’s an interesting story for fans who have some interest in their career. While I don’t think there’s anyone who would find this a disagreeable watch, I’m not sure it’s going to do all that much for people who aren’t already fan of their work. Thankfully, no such inhuman creature exists, so this is a moot point. Imagine! Not liking the Beastie Boys! The concept gives me the collywobbles.

It’s not immune to criticism, I suppose. It’s not exactly a warts and all expose, but then again there doesn’t really appear to be all that many warts to be exposed on these guys. They seem almost universally well regarded as artists, with the only blemish being the unabashedly misogynistic lyrics of their first album which they have been suitably bashful and apologetic for pretty much since the start of the 90s.

You could also say, and again, let me pause for a minute to prepare you for the sort of galaxy-brain level insights that you come to this podcast for, that this staged performance of a stage show, recorded on stage, comes across as a little stagey at points. Shocking, I know. There’s a few asides that were presumably at some point ad-libs that they liked and incorporated into the telling that are seem a little forced, however at this point I’m very much picking at nits.

I shouldn’t give the impression that it’s just them on stage delivering a PowerPoint presentation, there’s plenty of cuts to archival footage either as B-roll or to show an important or funny moment, and director Spike Jonze and the editors, Jeff Buchanan and Zoe Schack have done what they can to keep things visually interesting, despite the limitations of the format.

So, yes, minor quibbles aside, while the Beastie Boys Story is by no means life changing cinema, it’s a light, breezy, sometime touching and often funny look at one of my favourite artists and I enjoyed it a great deal.

Mulan

Even before seeing it, Mulan comes with several problems: from the egregious $30 RENTAL fee, on top of the base subscription to Disney+, to watch it; to Disney leaving cinema chains in the lurch by pulling it from theatrical distribution; a largely white, Western production team; the star seemingly supporting police brutality in Hong Kong; to the rather more important fact that some of Mulan’s filming took place in Xinjiang, where the Chinese Government has put a million Uyghurs into “Vocational Education and Training Centres”, which is a very strange misspelling of “concentration camps”. That’s Disney, folks, owners of “The Happiest Place on Earth”.

For now, let’s get to the film: a live-action remake, of sorts, of Disney’s own 1998 animation, Mulan is based on the 6th century “Ballad of Mulan”, which tells the tale of a young woman called Hua Mulan, who disguised herself as a male soldier in order to fight in the Imperial Army.

Northern China is threatened by an invasion of Rourans, led by Böri Khan (Jason Scott Lee), which I assume would be our current Prime Minister’s warlord name. He is helped in this by Gong Li’s Xiannang, a shape-shifting witch, who has allied herself with the Khan so that she can receive the reward of living in a society where she isn’t persecuted for her powers (though the film seems to avoid answering the question of why she doesn’t just conquer China herself). The Emperor (a horrendously wasted Jet Li, whose role almost entirely consists of “right, sit here in this silly chair for a while”) orders conscription for the army, and when the officers enforcing the decree visit Mulan’s village, she pinches the armour and sword of the only male in her family, her disabled father (Tzi Ma, apparently now the Chinese every-Dad) and offskis to the command of Donnie Yen’s Commander Tung, passing herself off as Hua Jun, a male soldier.

She then takes part in an uninspired training montage that lasts forever, and is, it seems, utterly pointless and misguided anyway, beyond showing that Mulan’s a bit nifty with a spear, as, despite her training in the infantry, her unit’s first battle shows them suddenly to be cavalry. It’s well thought out, this film. Talking of well thought out, by this point the film has established comprehensively that the Khan’s army, with the witch’s help, is unstoppable, with fort after fort falling easily, with not a single survivor left. They’re simply portrayed as too powerful, so any resistance to them at all at this stage would stretch credibility beyond breaking point.

Naturally, Mulan’s squad of infantry-trained cavalry fight them to a standstill.

Then Mulan shows off her General-level military nous by tricking the Rouran army, apparently unfamiliar with snow, despite coming from a place with snow, into bringing down an avalanche upon themselves, which looks every bit as stupid as that sounds, and is clearly just there because it’s in the animation (or so I believe). But it doesn’t matter, because it was all a diversion! And now the Emperor is in danger, and Mulan, just kicked out of the army for being a woman, is now kicked into the army to lead it.

A big fight ensues, which includes, amongst other things, a scene in which some of Mulan’s comrades demand that she locks them into a strange, valley-like chamber of dubious purpose, with their enemies, despite said enemies having been shown multiple times to be capable of running directly up sheer walls with no extra equipment.

It’s all so stupid, and so very, very dull, with the filmmakers clearly being concerned with looks above anything, and everything, else. And undeniably Mulan does look good, but in a very sterile way: everything is colourful and beautiful and pristine, and therefore horrible and free of any substance. The ridiculous grandeur of the Imperial Palace might invite a social commentary, but there’s no reading of social inequality in a feudal kingdom when the village of the farming peasants is also pristine, and their clothes perfect, beautiful and riotously colourful.

Beyond “it looks quite nice sometimes”, there is absolutely nothing to commend Mulan, the performances least of all. Donnie Yen is terrible. Gong Li is terrible. Jason Scott Lee is particularly terrible, though to be fair he is given the absolute worst of the insipid, woefully basic dialogue. And Yifei Liu in the lead role is one of the least charismatic performances I’ve seen in good long while. Even the action is insipid and uninspired: many scenes, particularly in the finale, use a lot of the style of the wuxia films with which many are familiar, but there’s no flair or style to them at all, not an immense amount of skill, and absolutely no sense of fun. And I haven’t even got into the bizarre choice to take the Chinese concept of qi and, basically, turn it into The Force, let alone its stereotypes of Ancient Chinese culture. No wonder it has bombed in China.

Absolute pish. Avoid.

Ava

Jessica Chastain here plays Ava Falconer, an ex-army highly trained assassin that’s started to question her orders and her life decisions, much to her handler, John Malkovchs’ Duke’s displeasure, but more importantly, the displeasure of the boss of this particular outfit, Colin Farrell’s Simon.

After a particularly botched operation, Simon decides that Ava’s a liability that must be disposed of, while Ava attempts to reconnect with her family and ex-fiance back home. Hence, conflict.

While Ava has an impressive cast, they are entirely wasted in a script that is composed almost completely of cliches, and for all of Chastain’s talents, she’s not an action star and all of fights she’s involved with look exceedingly unconvincing.

As such, it’s very difficult to get into Ava, and so it comes as no surprise that I didn’t get into it. I’d checked out of this very early on, and so didn’t appreciate the moments that of character building that this sort of cast should be knocking out the park.

This is very much “Checking My Phone Consistently: The Movie”, and while it’s not abysmal it’s certainly unremarkable enough to recommend avoiding it.

Les Misèrables

The suburban Paris commune of Montfermeil is famous as the location of Monsieur et Madame Thénardier’s inn in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, and the place of its writing, and infamous in more contemporary times as the location of the “les Bosquets” banlieue, or housing estate.

It is here that Mali-born French director Ladj Ly’s Les Misèrables is set, a film that begins by showing throngs of people watching, then celebrating, France’s 2018 World Cup victory. Notable is the fact that many of these people are, or are children of, immigrants, largely from Africa, pointedly showing that, despite the belief of many, these people are French. That it then shows the title, which can be translated simply into English as “The Miserable Ones”, over the cheering crowds filling the Champs-Élysées, gives an equally pointed idea of Ly’s cynicism.

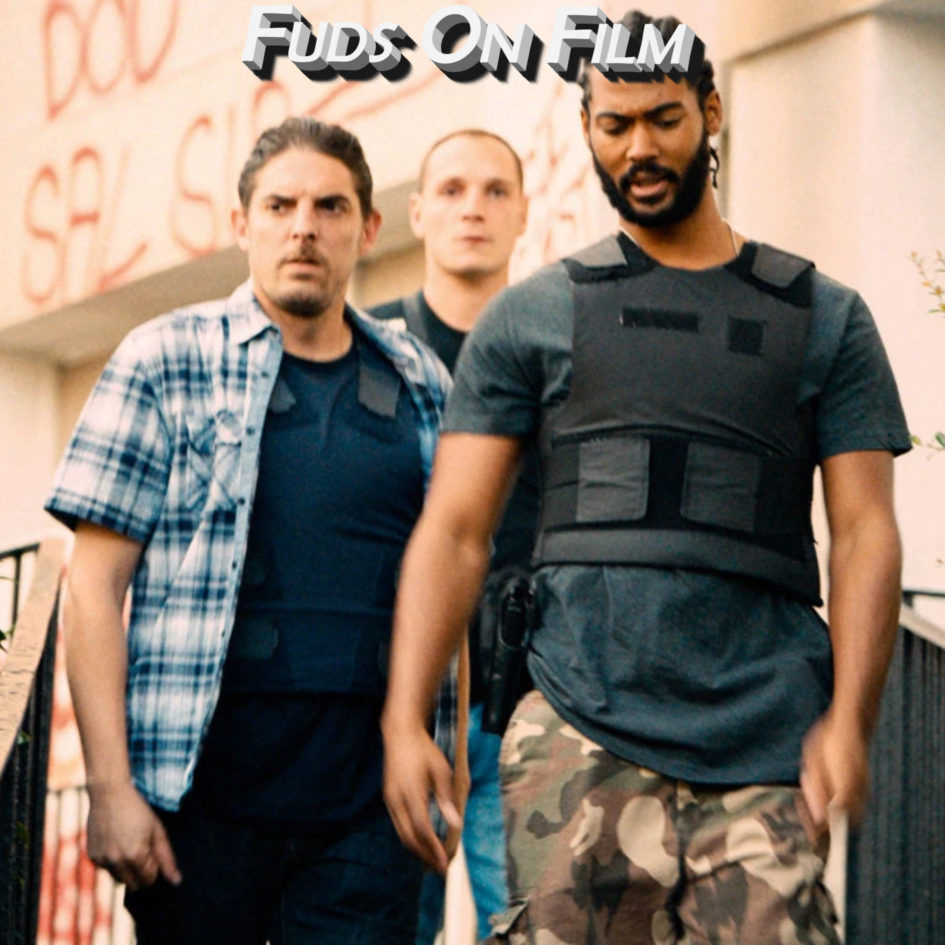

The story of the film begins with the first day on the job of newly-transferred police officer Stéphane Ruiz (Damien Bonnard), who will work with Alexis Manenti’s Chris and Djebril Zonga’s Gwada as a squad of the Anti-Crime Unit, whose job is, ostensibly, to prevent crime, but seems to actually consist of bigotry, racism, harassment, chauvinism and a general low-grade rottenness to the inhabitants of Les Bosquets, perhaps even extending to a little light corruption, if the sweltering heat doesn’t disincline them.

Ruiz is shocked by their behaviour, but as the new guy feels unable to do much about it, not least because the squad leader, Chris, seems to have the support of their captain, and the fact that within minutes Chris has dubbed him “Greaser” because of his hair to denigrate him and put him in his place.

A leisurely-paced first hour paints a portrait of the estate and the power dynamics at play within it, including the popular local mayor, Steve Tientcheu, and the assumed shadow power of Almamy Kanoute’s gangster turned faithful Muslim, Salah, and how they all interact with the police.

Tensions begin to rise, though, when an armed group belonging to a circus drive into the estate, threatening to burn it to the ground and commit murder if the kidnapped Johnny is not returned. Johnny, it turns out, is a lion cub, and he’s been stolen by Issa (Issa Perica), a quite committed juvenile delinquent. After identifying the lion-snaffler, the squad attempt to arrest him and head-off the danger of a race-driven battle between the circus workers and the Les Bosquets inhabitants, and that’s when things go, in the parlance of our times, tits-up. The squad are harassed and pelted with missiles by the group of young people Issa was playing football with, and in the confusion a police flashball goes off in Issa’s face. This is further complicated by the fact that the whole thing has been recorded by a drone owned by a child from the estate.

A series of stand-offs and chases then take place, as Chris and Gwada try to recover the drone’s footage, and the mayor, having got wind of the incident, tries to get a hold of it to serve his own ends, and a child’s potentially life-threatening injuries take a back seat. But even when things seem resolved, they’re far from it, and injured pride, frustration, anger and simmering-resentment set the scene for a violent finale.

It’s a powerful film, though you might be inclined to think that it’s a bit heavy-handed at times and over-the-top at times, however it would probably be useful to know that, in the director’s own words, “The whole film is witnessing what I witnessed as a teenager. Everything in it is inspired by real events, from the first scene to the very last scene”. That last scene, in fact, is based on something that Ly, who started filming and documenting Les Bosquets at 17, actually filmed,: it is even shot in the very stairwell where the incident took place. And the lion thing really happened.

Les Misèrables is, perhaps surprisingly, relatively balanced, especially in the figure of Ruiz as the decent police officer. Again, in the director’s own words, “The idea was not to take sides against the police, despite everything that happened in reality. I wanted to be even-handed: everyone, people who live on the estate and the police, they are all ‘les misèrables’”. This is not to say that the police are let off, far from it, but the director could have chosen to excoriate them, but didn’t.

The film brings to mind Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 La Haine (an acknowledged influence on the director), and there’s a real vitality to Les Misérables, and a real sense of place to its depiction of Les Bosquets, much of that owing to Ladj Ly’s documentary background, and some also to the 200 extras, every single one of whom lives on the estate. Where it perhaps suffers is that, while the banlieue certainly has a character, for the featured humans that’s much less the case: it would be great to see an exploration of the bullying, small-minded Chris, and even more so the clearly-conflicted Gwada, a child of African immigrants himself, but content to be complicit in his sergeant’s behaviour. It’s a place that probably deserves a TV series, one that could more fully explore its interactions, and the internal and external factors that influence it. But it’s certainly something I very much recommend watching.

I’ll just finish with a passage from the preface of Victor Hugo’s novel that gives an excellent flavour of Ladj Ly’s message:

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilisation, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age – the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night – are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.”

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply