In this month’s round-up episode, we take a look at Enola Holmes, Irresistible, First Cow, Console Wars, The Platform, and Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Check it out!

Download on Spreaker | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

Enola Holmes

So, it turns out there’s another scion of the Holmes family, at least as far as Enola Holmes is concerned. The entirely fourth wall destroying Enola, played by Millie Bobby Brown, is the younger sister of Henry Cavill’s Sherlock and Sam Claflin’s Mycroft, and had been growing up alongside her mother, the unconventionally strident Eudoria, Helena Bonham Carter, receiving a diverse education that encompasses both mystery solving and jujitsu, however it seems that things will change markedly when Eudoria goes missing.

Guardianship falls to the chauvinistic Mycroft, who would sooner have Enola shipped off to finishing school to become a “proper” lady, which holds little interest for Enola. She resolves instead to head to London on the trail of Eudoria, having uncovered a hidden message and stash of cash. On the journey she becomes embroiled in the problems of the young Viscount Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge), on the lam from a be-bowler-hatted thug. As it happens, both their problems are intertwined, leading to a begrudging respect between the two, despite the vast gulf in capability between them as they unravel these threads.

And, well, so it goes, in relatively predictable but not unenjoyable style. It’s a light, breezy, Young Adult twist on the Sherlock setting, and everyone involved, but particularly Millie Bobby Brown, plays events with a light enough touch that their charisma can paper over the gaps of a somewhat meandering plot that’s perhaps a bit too heavy on hammering home an important, but not all that well integrated feminist message.

That’s by no means enough to ruin a perfectly entertaining film. One that’s not going to revolutionise cinema by any stretch, but it’s more than enjoyable enough to pass a couple of hours.

Oh, and if you need any further examples of how copyright law is broken, The Conan Doyle Estate filed a lawsuit against Netflix over the film, claiming it violates copyright by depicting Sherlock Holmes as having emotions. This is silly, as is a lot of Enola Homes, but a little bit of silliness is not unwelcome at this juncture in history.

Irresistible

With apologies to the Wikipedia article, “Irresistible is a 2020 American political comedy film written and directed by Jon Stewart. It stars Steve Carell, Chris Cooper, Mackenzie Davis, Topher Grace, Natasha Lyonne, and Rose Byrne. The film follows a Democratic strategist who tries to help a local candidate win an election in a small right-wing town.”

Really, it’s problem is that it’s nowhere near funny enough, lumbered with an opening stretch that’s all troped up in service of a recontextualising, but silly, twist in the last ten, fifteen minutes or so. To be fair, it comes to life a bit at that point however it’s nowhere near worth suffering through a fairly dull eighty minutes to reach. Stewart would, we feel, have been better served with a more documentarian exploration of campaign finance reform, which is clearly what he was interested in. Bit of a swing and a miss, sadly.

First Cow

Which came first? The Cow, or the Egg? It’s that question that First Cow seeks to answer, and does a surprisingly terrible job of it.

Set in the before times of 1820s Oregon, John Magaro’s Otis “Cookie” Figowitz is a mild mannered cook for an unruly bunch of fur trappers, who stumbles on Orion Lee’s King-Lu, who’s on the run having killed some Russian bloke. After striking up a friendship, they go their separate ways only to meet up down the line at Fort Tillicum, after Cookie takes his leave of the trappers.

They chum about for a while before learning that Toby Jones’s Chief Factor has shipped in the territories’ first cow. They reason that the fresh milk could be used to make baked delicacies the likes of which the territory has never seen, on account of it being a largely untamed wilderness with no baked delicacies whatsoever. Sneaking in at night to milk the cow, their produce is a roaring success, however the increased demand risks drawing the unwelcome attention of the Factor and his brand of frontier justice. Some chasing may be involved, which may or may not tie in with the leisurely told framing device of Alia Shawkat digging up two skeletons in the modern day.

I’d heard good things about this film coming into it, but then again I’d heard good things going into Kelly Reichardt’s previous Certain Women and didn’t get a lot of joy out of that. I have broadly the same things to say about this as I did that, so perhaps it’s just the case that her style is not my cup of tea.

There’s a lot in here that I can appreciate, at least. The cast give uniformly believable performances of believable characters, given the time frame, and it looks great. It’s just that the entirely intentional slow pacing of the film and straightforwardness of the story just wasn’t connecting with me the way that it seems to have done for others. It’s all just a bit too minimalist for me. Maybe if it had more dubstep, or if the cook turned out to be an ex-Navy SEAL who must stop a group of mercenaries taking over a warship it’d be more my speed. It is important to recognise that I have no taste.

This is a well made film, for sure, and I’m sure there will be a great number of people more receptive to its arthouse charms than I was, so I shall not denigrate it, other than to say it didn’t do a lot for me.

Console Wars

Ah, Console Wars. This is very much in our wheelhouse: a documentary about how Nintendo was the worst and the smart, handsome folk had Mega Drives… Oh, and if it gives me plenty of irritations to moan about on the podcast (and it does), then that’s all to the good.

Based on Blake J. Harris’s (not particularly well-received) 2014 book of the same name, Console Wars, attempts to chronicle the battle for home videogame dominance in the United States after the video game crash of 1983, with the plucky upstart Sega and their Genesis shocking the arrogant, dominant Nintendo, who, with their NES, were the home videogame market in the USA in the late 1980s. Unlike the book, which presents its story in a series of reconstructed (i.e. made-up) conversations and meetings, the bulk of this documentary allows the prominent players at Sega and Nintendo to tell their own story in a series of talking head segments, often accompanied by 8 and 16-bit-style animations (that look considerably better than anything actually did on the consoles at the time). This makes for an interesting story, particularly when the likes of Howard Lincoln are still clearly salty and dismissive of Sega.

Alas, I was too annoyed by the film to really enjoy it. One of the most frustrating things about this documentary is how US-centric it is. Part of that, even a large part, is understandable and necessary: the primary adversaries in the story are the US arms of Nintendo and Sega, and the video game crash that played such an important part in giving Nintendo an opportunity with the NES was a US phenomenon, that crash not occurring in Japan or Western Europe (consoles hardly being a thing here at all at the time, with computers being the favoured gaming device). But these things weren’t happening within a bubble, yet the documentary barely even pays lip service to events in Japan, not even the sales figures or relative successes of the consoles there.

It’s remarkable the number of times I don’t walk around to the side of someone’s head while they’re talking to me to get a better look at their ear. Call me weird if you must, but when someone is telling me something I’m quite content to look at their face. But Console Wars (along with almost every other interview piece in the world, it seems) indulges in that spectacularly irritating conceit of having two cameras on people during an interview, and cutting to shots of their profile FOR NO REASON, though we are, at least, largely spared enlightening close-ups of knees, or They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead’s bizarre forehead-centric framing.

While I’m not saying I am advocating giving a slap to both the people who film or edit interviews like this, and the people whose attention span is so short they demand it (this is a lie, I am advocating precisely that), if you need something more visually stimulating, then the animations I mentioned are there: there’s no need to show me the back of someone’s head unless what you’re making is a hairdressing documentary.

In the interests of not making what I honestly thought would be a quick review even longer, I’ll just list my other irritations:

A guy had a moustache after Vietnam. Cool story, bro.

The film explains what SoJ and SoA are abbreviations for, despite it being blindingly obvious from context, but regularly talks about 16-bit technology without ever explaining it.

The visuals are either poorly matched to the conversation, or are deliberately done to undermine it, and I can’t decide which, though I think poorly matched (e.g. a comment about Nintendo selling to very young kids accompanied by footage of the notoriously difficult DuckTales)

And not irritation but bafflement: “It’s comparable to the launch of Madonna’s Sex book, y’know, Sonic 2sday?” There’s a sentence that needed interrogation.

The corporate intrigue and rivalry should be compelling, even riveting, but somehow directors Blake J. Harris and Jonah Tulis have managed to make something mostly annoying. Crazy.

Finally, unrelated to the documentary, really, but I learned that hedgehogs aren’t a thing in North America, and that US Sega’s adverts were rubbish: no doubt those who are really into Sega have come across these before, but while I was familiar with “Genesis Do What Nintendon’t”, I’d never heard the apparently famous “Sega!” before, and it’s crap, and certainly no Jimmy and The Barber. Get a Cyber Razor Cut!

The Platform

Iván Massagué’s Goreng awakens in a prison quite unlike any other. Well, a Vertical Self-Management Center, to be pedantic. His cellmate, or perhaps floormate, is Zorion Eguileor’s Trimagasi, a curious older gentleman who informs him that they are on level 48, a decent enough level, and they shouldn’t go too hungry or have to resort to cannibalism just yet.

You see, the food in this hole comes down from level zero, where an extraordinary feast is prepared for the higher levelled inmates to gorge on, for a few minutes at least, then the platform is lowered to the next level. All the way down to… Who know how far? Hundreds, at least, although by that point, of course, there’s no food left.

Troubles arise when, on the monthly shuffling of the inmates positions, Goreng and Trimagasi awake on level 171, which, it turns out, is more or less the level where resorting to cannibalism seems like a solid option. Thankfully Goreng is saved by a deus ex crazy lady, as Alexandra Masangkay’s Miharu re-appears, a women travelling down on the platform in search of her daughter.

There’s another couple of vignettes as Goreng awakens on level 33 with Antonia San Juan’s Imoguiri, who’s trying to convince people to ration their food to allow everyone to survive, and then later with Emilio Buale Coka’s Baharat with whom he and Goreng try to get a message to the Administrators of the facility that… well, it’s something about a panna cotta. Probably meant as a metaphor.

Of course, in terms of the structure so dominant in the movie the message is a fair bit clearer, as this isn’t a film that’s making its political points particularly subtly. Where it falls apart a little as an allegory is the text of it – there’s not much in the way of remotely plausible, feasible or satisfying answers to the how, what, where, and why of this prison, and it seems all to eager to plaster over these gaps with buckets of blood.

However, for the strong of stomach, there’s an entertaining movie to be found here, told with the same sort of impressive low-budget minimalism of something like the setup of_Cube_, with the politics of Snowpiercer. It’s by not without its flaws – there’s a lot of plot threads thrown out that don’t really weave together into anything ultimately meaningful. It’s probably a film that’s better described as “interesting” than “good”, but I think that’s enough to recommend it as a curio.

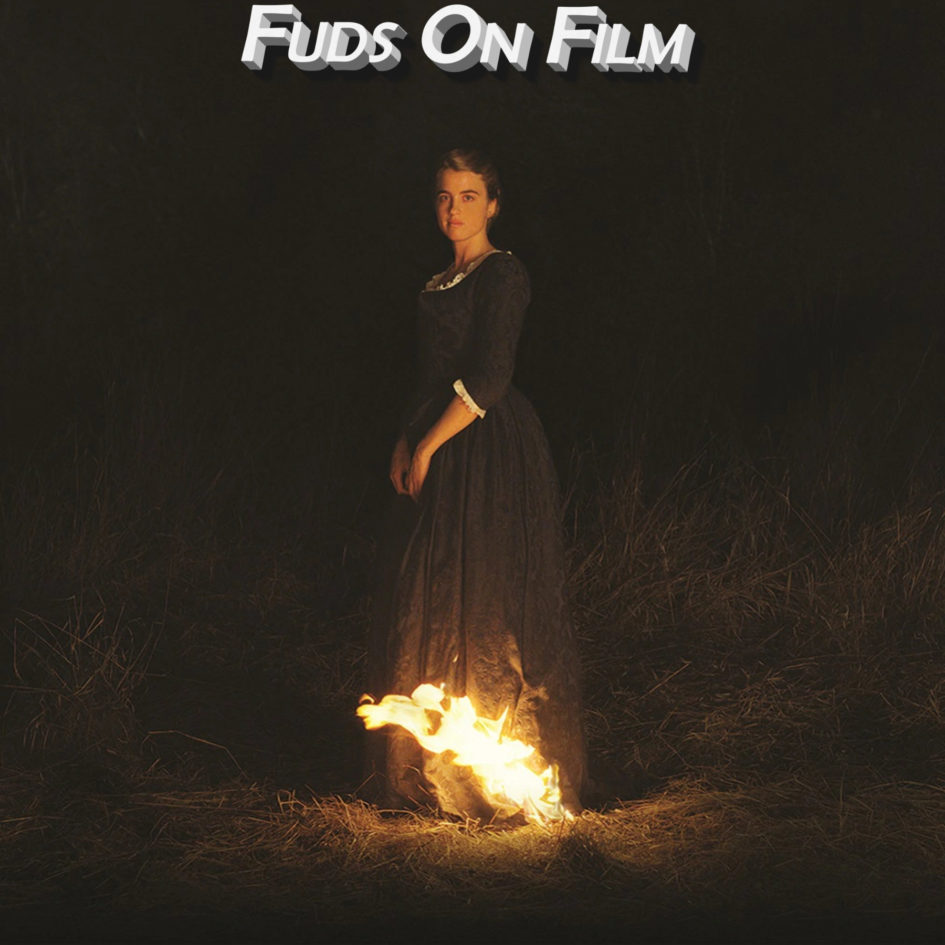

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Girlhood and Tomboy writer-director Céline Sciamma’s latest film, Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (Portrait of a Lady on Fire) finds us in the 18th century, as we accompany Parisian portrait painter, Marianne (Noémie Merlant), to the island home of Valeria Golino’s Countess, where she is to paint the likeness of her daughter, Héloïse (Adèle Haenel). This portrait is to be sent to her Milanese suitor, and an unhappy Héloïse refused to sit for the previous painter. Therefore Marianne, presented to Héloïse as a companion, must observe her subject stealthily, committing her features to memory to be painted later.

Marianne’s keen observation does not itself go unnoticed, and the act changes both the watcher and the watched, an erotic observer effect, and the two begin a romantic relationship, though one doomed from the beginning due to circumstance of time, social standing and gender.

Portrait can, and does, work simply as a compelling, beautifully-shot and beautifully-acted romance, but there’s so much more there. The film has both female perspective and female gaze, and continues Sciamma’s wonderful knack of making the story of a specific character (or, here, characters) universal, with her attention to detail in things often as small a glance, or lack thereof, or just a few words of dialogue, speaking volumes, and to many, as Marianne and Héloïse’s relationship plays out. There’s a lot of socio-political critique there, for example the subplot involving the maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), her unwanted pregnancy and the methods she must try to exert control over her own life and body.

Claire Mathon’s photography is beautiful, presenting Portrait of a Lady on Fire almost as a series of paintings, artistic and mesmerising, yet without the lack of life or dynamism that so crippled Peter Webber’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, a film that captured the look of Vermeer’s work but asphyxiated its world in so-doing: that is emphatically not the case here, where the wild seas and cliffscapes, the blustering wind and the fierce heat of Héloïse and Marianne keep the film gloriously, joyously alive.

Music, and its absence, play a huge part in the film’s success, too. We, understandably, take for granted the ability to listen to music anywhere and any when, but Héloïse is starved for music, another desire, a need, that her life denies her. Fittingly, Sciamma denies the film music also, using only diagetic sound – the wind and waves almost becoming characters – except for the few moments where music is played in the film’s world, and one spine-tingling scene where spontaneous, ethereal, vocal sounds become a song sung by a group of women on a bonfire-lit night: the lack of music elsewhere makes this incredibly effective, even more so as it accompanies a lingering stare between Héloïse and Marianne in which their feelings are finally, almost palpably, transmitted.

I’ve mentioned already that it’s beautifully acted, but the final scene is something else altogether, and possibly one of the most incredible things I’ve ever seen, despite involving a character sitting, and uttering no dialogue (I’ll describe it no further, and leave you to discover it for yourself).

It’s such a beautiful film and one that, now I talk about it, I think I like even more than I realised while watching. Obviously, therefore, I recommend it.

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply