The phrase “Hollywood Royalty” is not uncommonly used, though it’s usually quite hyperbolic (though, unlike actual royalty, it’s likely that anyone to whom it is applied at least has a modicum of talent and value to our world, and an argument for continued existence). In some cases, of course, the phrase is entirely justified, and certainly in the case of our subject today, a member of a four-generation film and theatre dynasty – amongst whom writers, directors, actors, and voice coaches – beginning in Canada and expanding to the United States, Ireland and the United Kingdom, with a stop in Italy along the way.

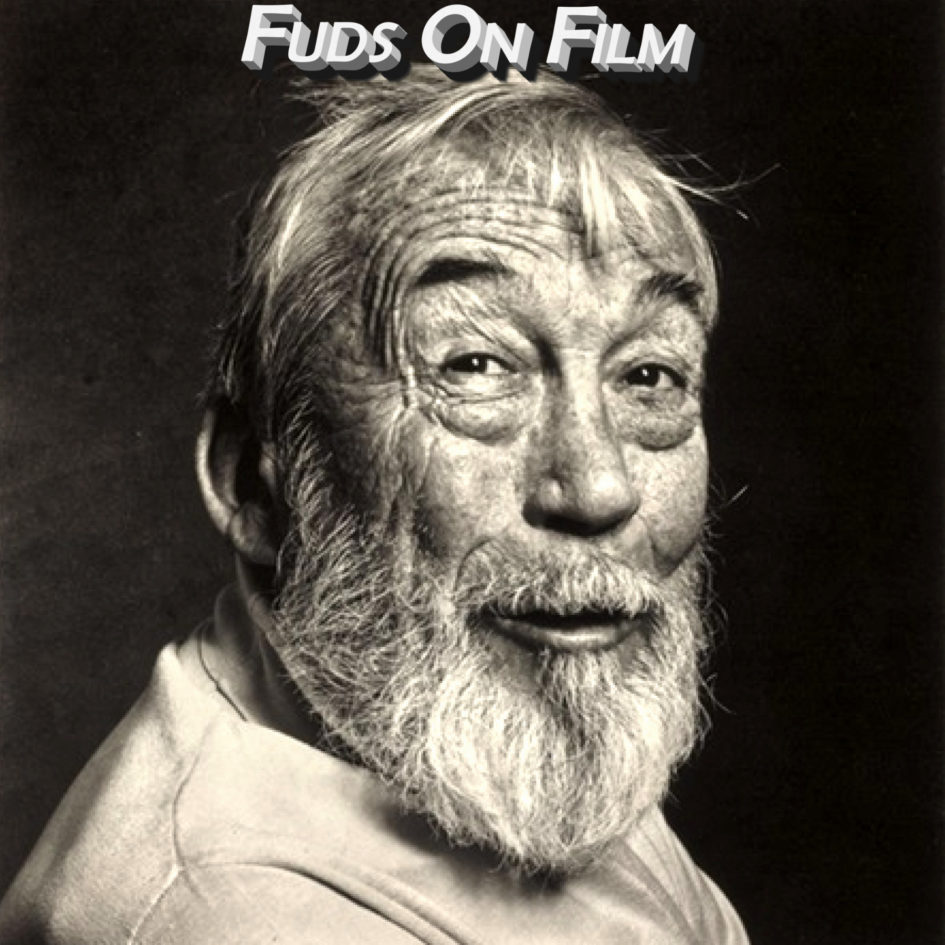

Three of the four generations have a winner of an Academy Award, including our subject, inarguably the most notable member, and the most storied. That person is the actor, director and writer, John Huston, whose film career spanned forty years. As well as acting in a good many films and directing 37, he displayed a social conscience, co-founding the “Committee for the First Amendment” before renouncing his US citizenship and moving to Ireland due to his disgust at the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s. On a personal, and utterly inconsequential, note, he also holds a unique place in my own film-watching career, being one of the directors of the only film that, as an adult, I’ve begun but never finished.

We’ve previously covered one of the films he wrote, Sergeant York, in our Howard Hawks episode, and discussed films in which he had acting roles in the form of Chinatown, The Hobbit and The Return of the King (the awful Rankin/Bass animations, for clarity), as well as his starring role in the much-delayed Orson Welles film, The Other Side of the Wind. Our business here, though, is Huston as director (though, by sheer coincidence, 5 of our 6 selected titles were also written by him, with the 6th being written by his son: royalty really does like to keep it in the family, doesn’t it?).

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

Starting off strong, with a film that’s commonly held up as strong contender for Huston’s best film. This adaptation of the Fallout: New Vegas DLC Dead Money sees Huston’s frequent co-conspirator Humphrey Bogart as Fred C. Dobbs and Tim Holt as Bob Curtin down on their luck in mid 20’s Tampico, after being scammed out of their pay on an oil rig construction project by an unscrupulous boss. Imagine that. In a grimy hostel, they meet an ol’ timer, Walter Huston’s Howard, a gold prospector who claims to have found fortunes and lost them, but feels there’s one last find waiting for him in the Madres.

The three team up and raise the stake money for the initial investment in gear for an expedition to the mountains, and true to his work Howard finds a spot that’s rich for the taking, even if that taking is long, laborious, difficult work. Howard also warns that gold has an effect on man’s mind, certainly when combined with the isolation of working in such isolated conditions. While Dobbs and Curtin dismiss this, sure that their partnership will remain strong, it’s not long before Howards proven right about this too.

It’s not just simple greed that starts gnawing at them, Dobbs in particular, but some interlopers into the situation, such as Bruce Bennett’s James Cody who tracks Curtin back from a resupply trip, unconvinced by the tale of them being game hunters. He wants in on the action, but before the trio can get round to declining this invitation with a terminal refusal, a group of bandits appear. In the gunfight that follows, before they are seen off by the Federales, Cody cops a fatal case of lead poisoning.

Reasoning that the situation is getting too hot, Dobbs, Curtin and Howard resolve to divide up the spoils of the mine and head back to civilisation, but Howard is called away by local villagers to provide medical aid to a sick child. Without a mediating presence, Dobbs and Curtin have increasingly heated arguments, up to the point where a crazed Dobbs shoots Curtin, resolving to make off with all of the gold. However, the bandits may have other plans, while Curtin isn’t quite as dead as Dobbs thinks he is, having managed to crawl away, saved by the local villagers and Howard’s ministrations. Somewhat recovered, they go after Dobbs, and then the bandits, where they can reclaim their mules, but not the gold, now scattered to the four winds.

While there’s a lot of things happening in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre to fulfil its’ billing as an adventure flick, the most interesting things by far isn’t any of the shootouts or mine cave-ins, fine as they are, it’s Humphrey Bogart muttering to himself as he falls deeper into a grip of paranoia, suspicion and assorted ill-intents, which is a joy to watch and if anything, the film could do with more of it. Tim Holt’s Curtin is a reasonable blank slate for Bogart to bounce off off, although I don’t think he’s able to play at the same level as Bogart or, John Huston’s dad, which is perhaps less a criticism of Curtin and a reflection of the talents of Bogie and Huston Snr.

So, a good adventure film with great performances and a solid underpinning exploring how greed can destroy your character, set in the beautiful, rugged Mexican mountainside. What’s not to love? Not a lot. It’s not exactly breaking with film critic dogma to say that The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is, y’know, good, but it is what it is. I would say that this is a film you must watch before you die, but only because watching it after you are dead is going to be tricky.

Huston worked with Humphrey Bogart again in his next film, Key Largo, released the same year as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and notable for upping the number of women from his last to “any”. There are in fact two main female roles here, which, given the small number of characters, actually makes them a more significant proportion of the film than you might expect.

One of those women is Lauren Bacall, in her last onscreen pairing with Bogart, as the widow of a soldier who died in the latter days of World War II. Bogart plays Frank McCloud, the soldier’s commanding officer, who has travelled to Key Largo in Florida, and the hotel that Bacall’s Nora runs with her father-in-law, James, played by Lionel Barrymore, to answer such questions as they may have about the soldier and his death.

On the day of his arrival, he finds the hotel privately booked by some “special” guests, a party of gentlemen from Milwaukee who are in Florida to fish, and who are absolutely NOT gangsters, despite their appearance, speech and general demeanour. Businessmen from Milwaukee, capisce?

A hurricane approaches Key Largo, both metaphorically and literally, and tensions within the hotel rise even as the barometer drops, as we discover that the totally-not-gangsters, guv, honest turn out to be gangsters, led by Edward G. Robinson’s Johnny Rocco, a mobster expelled from the country in the 30s, and in Florida from Cuba for the purposes of a business transaction. This small group of mafiosi hold the other inhabitants of the hotel hostage while waiting for the buyer of their merchandise to arrive, before forcing Frank to pilot their commandeered boat back to Cuba.

Although she’s making puppy-dog eyes at him when Frank first arrives, there is less tension between Bacall and Bogey than in their three other films together, as here her character looks towards Bogey’s more for comfort than romance, though the latter is potentially on the cards. In fact, Bacall’s is a fairly minor role, though her character is important as she quietly implores Frank to do the right thing come the end, and it’s the other female character that really stands out, a terrific performance by Claire Trevor as Gaye Dawn, as Rocco’s former paramour.

Edward G. Robinson drew a lot of praise at the time and over the years for his turn as tough guy mob boss Johnny Rocco, but for me he’s… fine. A pretty much generic gangster, really, without, here at least, a lot of screen presence or menace. Where he’s much better, though, is in the film’s stand out section, as the hurricane batters the hotel, and the hard man begins to become nervous, then unmistakeably afraid. “You don’t like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don’t you? If it doesn’t stop, shoot it.”, Frank goads him, his composure having slipped.

In this sequence is also found the film’s stand out performance, an awkward, discomfiting scene in which the terrified, sad, alcoholic Gaye is tormented by Rocco, and forced to sing a cappella to earn a drink. Denied the opportunity to rehearse her song by Huston, Trevor performed it in one take, the actress making all watching decidedly uncomfortable as Gaye becomes conscious of the words she’s singing – her most famous song from her days of popularity as a singer, about a woman in love with a cruel man – and their uncanny resonance with her own life, and her voice falters.

It’s all passably entertaining, but a minor work for all involved, Claire Trevor aside, and, though I wouldn’t try to dissuade anyone set on watching it, with so many other films in the world, I wouldn’t recommend it either. And I especially wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who, like me, has always deeply disliked the film, TV and, let’s be honest, real life, trope of “it’s perfectly fine for police officers to shoot and kill someone just because they’re running away”. It’s a subplot in the film, but the pardoning of the cop at the end of the film with a hand-wavey “it’s fine you killed two innocent people because bad guy” is beyond infuriating to me.

Minor work as it may be, though, Bogart is as great as he usually is (I really could watch him in anything), and for that alone I may, on second thought, rescind my refusal to recommend it. The world-weariness and cynicism of someone who went to war because “I believed some words… and they went like this: ‘We are not making all this sacrifice of human effort and human lives to return to the kind of world we had after the last world war. We’re fighting to cleanse the world of ancient evils, ancient ills’” but now no longer does believe them oozes from every pore; a disillusioned man fed up of death, and of sacrifice, who won’t kill the gangster when given the chance because “one Rocco more or less isn’t worth dying for.” (Those words, by the way, were from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s State of the Union Address the month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, words that would have had particular resonance for US audiences at the time, and Rocco’s not recognising them would have had real significance.)

Right, that sorted, I can now just wonder why Huston, or whoever it was, decided that the film needed introductory text about the Florida Keys, when any part of it that is relevant (which isn’t much) is within the body of the film. Such decisions baffle me.

Katharine Hepburn’s Rose Sayer and her brother Sam are busy attempting to bring Jesus to villagers in 1915 German East Africa, which suddenly goes rather poorly when WW1 breaks out and ze Germans forcibly conscript the villagers, in the process as good as killing Sam. With Sam dead and their mission over, Rose goes along with local mine engineer / handyman Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart), as he makes his escape with the mining and blasting equipment that the Germans would otherwise seize on the banged up little tramp steamer The African Queen.

The two come from very different classes, Charlie a cheery, practical greasemonkey and Rose being an upper-class, prim and proper type, and, well, I don’t think I need to tell you how that relationship is going to pan out over the course of the adventure.

Said adventure is a cockamamie plan devised by Rose to sail down the thought to be un-navigable Ulanga River, past dangerous rapids, falls and German fortifications, to sink the top-of-the-line German Königin Luise gunboat that’s been bothering the British war effort with some improvised torpedos made from Charlie’s explosive supplies. It’s a one in a million shot, so I don’t think I need to tell you how that pans out.

This is for the most part pure adventure bunkum, and I can see why it was so successful back in 1951. Now, there’s little point in critiquing the special effects from a standpoint seventy years later, but while you’re unlikely to see the rear projected shots as anything other than dated there’s more than enough actual on-site footage to keep the illusion up, this being another one of John Huston’s successful attempts to get the studio to pay for his travel desires.

I quite enjoyed this, for sure, although I’m perhaps a little confused by the very high esteem it’s held in. For sure, Hepburn and Bogart play the hell out of their roles and have decent, if not scintillating chemistry together here, but I feel they are a touch hamstrung by some very broad roles and characters, and some not too brilliant dialogue. None of it’s a deal breaker, but for me at least it’s not quite holding up to its reputation. And if you’re only going to give Bogart one Oscar, it’s very weird that it’s for this.

I suppose there’s other reasons to admire it from a technical or production standpoint, like the difficulty in wrangling Technicolor cameras in difficult locations, and the gastrointestinal challenges the location presented, but that’s very much divorced from the on-screen results of it which are good, but not mind-meltingly spectacular.

Still, a breezy adventure that’s well worth seeing have you not done so already.

Based on Tennessee William’s stage play, and adapted by John Huston and Anthony Veiller, The Night of the Iguana, or “Put down the fucking maracas!”, is a story of an emotionally fraught holy man unable to control his urges and demons.

Like the entrance to hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy, “Abandon all hope, ye accents who enter here” ought to be inscribed over the opening shots of this film. And I thought Kate “I’m totally a Brummie” Hepburn’s origin was laughable in The African Queen. Egads. For his Virginia clergyman, Richard Burton has toned down his Welsh lilt so that he mostly sounds English, and then there’s Deborah Kerr’s English Nantucket accent, and her grandfather’s Nantucket accent, also very English. Nantucket! Have you heard Massachusetts accents? They are distinctive, to say the least.

However, the inappropriate accents I set to one side and settled down to enjoy this tale full of unlikeable arseholes. OK, that’s a bit harsh: mostly full of unlikeable arseholes – there are about one and a half sympathetic characters. Chief amongst the disagreeable former is Richard Burton’s Episcopal preacher, T. Lawrence Shannon who, to put not too fine a point on it, can’t keep it in his pants, particularly when it comes to younger women. After an opening in which we see him furiously excoriating a congregation who, he believes, have come to his service out of prurient interest in his latest scandal, we soon find the now-defrocked vicar leading cut-rate bus tours in Mexico.

He has apparently been steadily working his way down the quality ladder of these tour companies, and his current employer is on the bottom rung, a rung from which Shannon is now himself hanging with one finger. So it looks promising for his employment prospects that he is doing little to deflect the advances of Sue Lyon’s smitten, underage Charlotte. The two getting cosy hasn’t gone unnoticed by Charlotte’s guardian on the trip, Grayson Hall’s Judith Fellowes, a miserable harridan who nearly gives herself a stroke having a conniption on the beach, stamping her feet as Charlotte, swimming with Shannon in the sea, ignores her.

After Charlotte is found in Shannon’s hotel room, Fellowes makes it her business to have him sacked, something a desperate and entirely rational Shannon attempts to evade by commandeering the bus, driving the party to a hotel owned by a friend of his, sabotaging the engine so that they can’t leave, and holding them circumstantially hostage so that he can prove to them that he really is a clergyman, not defrocked, and that he’s great and that they’d see how great he is if they only give him a chance. He is not exactly displaying joined-up thinking, though he displays a little self-awareness when he tells Charlotte, “I want to explain something to you… A man has got just so much in his emotional bank balance. Mine has run out. It’s stone dry. I can’t draw a check on it. There’s nothing left to draw out.”

This hotel is run by Ava Gardner’s Maxine (the one sympathetic character), whose hotel, it being out of season, is closed. But due to her friendship with Shannon, she reluctantly agrees to open up, and she’s more than a bit miffed when, shortly after the bus, Deborah Kerr’s itinerant, potless artist, Hannah, and her poet grandfather turn up, looking for free room and board while they make some money selling sketches or reciting poetry.

The tour group finally recovers the means to fix their bus, and depart, leaving Maxine, Hannah and a relapsed, drunk Shannon (and, in the hands of the Mexican beach boys, the goddamn maracas!) alone in the hotel. During a long night of the soul/iguana (please note: there are iguanas in this film, but, unaccompanied as they are by Johnny Adam’s singing Release Me, I am confident they are real, literal iguanas, albeit of metaphorical import), a raging Shannon is soothed by Hannah, and the two share some of their demons, though Hannah is further down the road than Shannon, so she becomes his emotional guide.

I assume Scott hated this, it being chock full of subtext, but I, for reasons I can’t readily articulate, really enjoyed it – there’s plenty to dig into here, and a lot of philosophising about the human condition. There are great performances all around, and, shockingly, everybody is cast largely age-appropriate, though this actually backfires for a 2021 audience, as comments about being forty from Kerr and Burton’s characters elicited a note of derision from me, a looking up of their bios on IMDb and a quiet, sad, “Jaysus.” Mid-20th century living was hard living.

Set in the late 1800’s, we find journalist and baker of exceedingly good cakes Rudyard Kipling, played by Christopher Plummer, being regaled with the tale of a now wild-eyed, half crazed ex-soldier, Michael Caine’s Peachy Carnehan, relating what he and his fellow lovable rogue Sean Connery’s Daniel Dravot have been up to since they last met, and it’s quite the shaggy dog story.

See, Dravot and Peachy had been bouncing about India since leaving the army, with a variety of petty criminal schemes that sees them on the verge of being kicked out of the country. However, they have one last gambit in mind, an audacious trip to head far to the north into what I think would be modern day eastern Afganistan, here called Kafiristan, with as many rifles as they can smuggle over the border. They intend on getting an in with a local tribal chief, training them in the art of war, and superior firepower, and fashioning their own nation state, once they’ve usurped the chief.

It’s a perilous journey, over treacherous mountain paths, but they make it and start their plan. Surprisingly this seems to be going much better than modern nationbuilding attempts in the area, but business really picks up when an arrow strikes Dravot, but doesn’t penetrate his bandolier. Because this film treats Afgans like they are credulous toddlers, they all now believe Dravot is effectively a God, Sikander, or the second coming of Alexander the Great. Hmm.

At any rate, this godhood supposition is confirmed by the high priests when they see Dravot’s Masonic necklace, Alexander the Great apparently having been a founding member of the mountaintop Afgan Lodge #69. Nice. With Dravot set as king and God, and full access to the treasury, it would seem that all they need to do is wait until winter passes and they can ride out with all the gold they can carry. That is, as long as Dravot doesn’t let the adulation goes to his head, and push the boundaries of what’s acceptable.

I watched this before, I now realise about a quarter of a century ago, and inasmuch as I can remember anything about it I thought it was a fun, Boy’s Own adventure, with spectacular scenery, and two of my favourite actors bouncing off each other in a yarn that’s not credible, but is entertaining. A sort of low-brow take on Lawrence of Arabia it was in my head. Now, on revisiting, all of that is still there, and I still enjoyed this.

However, it’s tough not to reappraise this somewhat now I’m older and have a rather clearer idea of the effects of British colonialism in the region, most of which we’re still dealing with today. That said, I’m just some goon on a film podcast, so I’m not going to get into that too much, other than to say if you start down that path of thought you’d be forgiven for wanting to sit The Man Who Would Be King out. Surprising, I know, what with it being a Kipling adaptation and all.

Separating that, if you can, you’re left with another solid adventure backbone elevated by Connery and Caine’s performance, although again they’re somewhat broad, but this feels more in keeping with the spirit of the thing than in The African Queen. Also, you may have noted that this podcast is prone to lapsing into the sort of Michael Caine impression that’s more of an impression of Mike Yarwood’s impression in the 70’s, or at best small parts of The Italian Job. Well, actually, no, this film has reminded me that it’s a highly accurate impression of Caine at all points in The Man Who Would Be King.

So, a somewhat caveated recommendation, but I’m still quite fond of it.

Our last film was also John Huston’s last, The Dead, an adaptation of a James Joyce short story, part of his collection The Dubliners. I can’t say I was looking forward to watching this – a costume drama about upper middle-class people in Edwardian Dublin, with a production quality that looked very like a TV movie.

I’m happy to report that within minutes my scepticism had evaporated and I simply began enjoying it instead. I can’t really tell you what it’s about, because I’m not convinced that it’s really about anything, beyond a reflection in the final act that all things must pass, in juxtaposition with the life and vitality on show in the rest of the film.

The main event is an Epiphany Party being held in a Dublin townhouse, where an extended family and some close friends have gathered, as they do every year, for the last celebration of the Christmas period. Nothing that passes is remarkable, but it’s all very believable: people catch up, others fret about the food, opinions are exchanged about cultural events, guests are called upon to recite poetry or, in the case of one elderly aunt, step repeatedly on cats, though everyone refers to it as “singing”. Must be a Catholic thing, I think, and I’m out of my element there.

The characters and dialogue, while perhaps bordering on the pretentious at times, all seem generally likeable or interesting, and no-one is too broad, even the nephew who likes alcohol far too much. The director (who shot this film from a wheelchair, with an oxygen tube to his nose) managed to place his camera intimately amongst the guests, trusting more to his son Tony’s script (really quite close to Joyce’s text) than anything flashy or technical to put the audience amongst this warm, pleasant and often humorous setting.

And really, that’s almost all there is to it, but I don’t want to diminish it by that – it was a very nice place to spend a while.

As the party ends, though, Anjelica Huston’s Gretta hears one of the guests singing a song called The Lass of Aughrim (fortunately this is not the cat killer, but a man with a most pleasant voice), a song which strikes her heart and brings up memories of her dead teenage love, memories which she later confides to her husband, Gabriel, in their hotel room. The film ends with her husband reflecting on this in voiceover: “One by one, we’re all becoming shades. Better to pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age”, comparing the future with the vital evening he has just enjoyed. Bit of a bummer, really, but touching nonetheless.

That’s it. It seems so slight, but I really liked it. I was even impressed by Anjelica Huston’s Irish accent, which was pretty near flawless, and for that I’m particularly grateful as I’m always on edge when I know that an actor is going to attempt a Scottish or Irish accent, because it’s rarely good. No such fears here, though. Indeed, the only slightly dodgy-sounding accents were genuine Irish actors who’d likely been living in England for a long time.

Really, the only issue I had with The Dead was the voiceover at the end, largely because it didn’t seem necessary for it to be framed as inner monologue. A very minor tweak to having Gabriel speaking instead to the sleeping Gretta and it’s sorted.

A final note on this (which to be clear I very much recommend), and that’s to draw attention to the scene in which, for some reason, the hostess feels compelled to say to one guest about another that, “to tell you the truth, she’s basting the goose”. This is not a euphemism I’ve heard before…

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply