We take a look at two mid-fifties creature feature responses to the advent of the nuclear age, with Godzilla and Them!. Will they hold up in Space Year 2021? Tune in and find out!

Download on Soundcloud | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

Godzilla

“As big as a gorilla” according to some, “as big as a whale”, like The B-52s’ car, according to others, the identity of the stage hand (or Toho publicity department employee, according to director Ishirō Honda) whose immense size created the portmanteau of gorira, gorilla, and kujira, whale, may be lost to time, but not the monster whose name he inspired: Gojira (anglicised to Godzilla). The legendary sea-beastie (or gorilla-whale) has appeared in more than 30 films, as well as TV series, comics and even a Hanna-Barbera cartoon (which was terrible, naturally).

However, it all began in 1954 with Ishirō Honda’s Gojira, made just nine years after the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the immense destructive capability of which, along with the terrifying long-term, invisible, effects are bound to have an effect on a country.

Three Japanese vessels are lost at sea, with few survivors, then fishing hauls begin to disappear. Something funny is going on in the waters around Japan. Just what is discovered soon after, when the island of Odo is attacked by a radioactive dinosaur, an ancient creature disturbed from its slumber by United States undersea hydrogen bomb testing. The survivors flee to Tokyo, demanding help from the government. Vessels continue to be lost, and all attempts to harm the creature with depth charges fail.

Eventually the giant Chewits-loving reptile arrives in the Japanese capital, emerging from Tokyo Bay and laying waste to part of the city. All attempts to defeat it are fruitless, from tanks and machine guns to missiles, and even an enormous electric fence. While one prominent scientist pleads with the authorities not to attack Godzilla but rather to study it, and learn how it survived such a massive dose of radiation, his protégé must deal with the moral quandary of his discovery, a device that will neutralise the beastie’s threat and save what’s left of the city, but will inevitably be turned into yet another uncontrollable weapon by those no-good bloody humans.

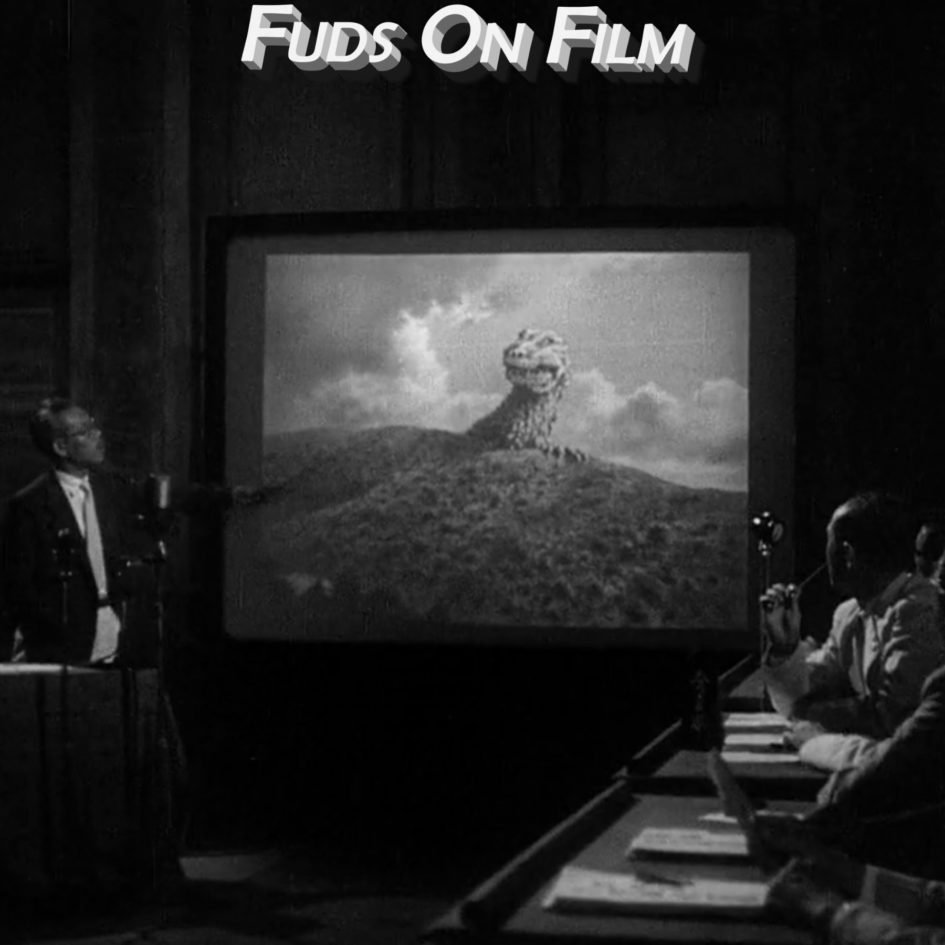

For a monster movie there’s not actually a great deal of monster on show here: it’s not, I think, particularly surprising that the effects work of a 1954 film with a budget of only around $1 million doesn’t hold up particularly well (though, to be fair to Toho’s first outing, at no point does the titular monster look anywhere near as goofy as the googly-eyed initial incarnation from 2016’s Shin Godzilla), but for a man in a big rubber suit it’s not actually awful, and it’s aided by Honda’s sparing use of the creature (later entries in the series may have demanded plenty of monster action, but in the original neither the characters, nor the audience, knew what Godzilla was, so both were on a journey of discovery). Rather it’s the “model” shots that have withstood the test of time particularly poorly. Well, I say “model” shots. Toys. They’re toys, particularly the mangled helicopter and the trains.

Sound design can go a long way in papering over cracks, though, and so it is here: Godzilla’s roar is organic but alien, and would definitely put the shit right up you if you heard it in real life. But beyond the iconic creature, what stands out in Godzilla are the themes.

There’s a film paper or ten that could be written about the differences between the original Japanese Godzilla and the US adaptations, especially in this first film: Godzilla represents the dangers of the nuclear age, particularly the incomprehensible destructive power of nuclear weapons. It is unstoppable, uncontrollable and life-threatening, a genie well and truly out of the bottle. In contrast, US takes, if they referenced atomic bombs at all, did so sparingly, and saw Godzilla become a weapon: dangerous, certainly, but a necessary evil against other aggressors. No subtext there at all, no sirree.

The Japanese-produced films changed tack eventually, turning Godzilla into a hero and pitting it against other monsters, which is undeniably better if what you want to make is a monster movie, but if you want to actually say something, as it seemed Honda and the studio, Toho, did in the mid-1950s, then this is clearly a far better way to do it, though a touch more subtlety than “walking H-bomb” might have been nice.

The earnestness of the film, and its very on-the-nose themes and metaphors, remove some of the watchability from it, at least for me, but it’s a fascinating insight into the psyche of a nation, and of the overriding, and entirely legitimate, fears felt by its populace. It’s best to consider it apart from most of its sequels (with the exception of 2016’s Shin Godzilla, which updated this film’s central allegory from nuclear weapons to nuclear power in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster), especially as its what is left in Godzilla’s wake – burning cities and irradiated children – that is the true driver of emotion.

Long before James Cameron was making films, it was Godzilla, and what Godzilla represented, that truly was the force that can’t be reasoned with, can’t be bargained with, that doesn’t feel pity or remorse or fear, and that absolutely will not stop, ever, until you are dead. If you like your monster movies with a heavy dose of introspection, existential fear and post-war commentary then this is the monster movie for you.

Them!

While Japan was dealing with the aftermath of having nuclear bombs dropped on them, even before the full onset of the Cold War and the shadow of mutually assured destruction there was concern in America about the responsibility of opening the atomic edition of Pandora’s Box.

Thus, Them! also released in 1954, where James Whitmore’s New Mexico Police Sgt. Ben Peterson is tasked with figuring out what’s caused a trail of destruction and death out in the desert, including a holidaying FBI man. This beings James Arness’ Special Agent Robert Graham on board and before long, for reasons unclear to the detectives but transparent to an audience that’s seen the poster, myrmecologists Edmund Gwenn’s Dr. Harold Medford and his daughter, Joan Weldon’s Dr. Pat Medford.

At the risk of shortcutting this a bit too radically, they work out that the trouble is being caused by ants of unusual size, which brings with it unusual strength and ferocity. Thanks, Oppenheimer! Now you have become Death, maker of large ants. The authorities work quickly to eradicate this threat, but discover that two new queens have already flown the nest, and so begins a race against time to track down and destroy them before humanity is supplanted as the dominant species, ending, as things so often do, in a Los Angeles storm drain.

This was a massive success for Warner Bros. on release, and I want to say up front that I did quite enjoy watching this, but it is hard to check the decades long accumulation of creature feature genre baggage at the door and take this entirely at face value. I mean, it’s only a couple of decades later that this and its genre-mates have been parodied out of existence by the likes of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes and replaced in the cinemas by disaster films. Which is ironic, as most disaster films follow fairly similar action and pacing pathways as these films, just replacing the giant ants of whatever with fire, or water, or just bees of a normal size.

Anyway, a lot of Them! is not about taking a flamethrower to a delightfully chintzy toy ant, or knocking over even more delightful toy vehicles, and is instead something more akin to a criminal manhunt headed by David Attenborough, and you know what, I’m here for it. It’s refreshing to see this played entirely straight, and with the obvious exception of the Oscar nominated special effects, and scientific understanding of radiation on DNA, it doesn’t feel all that dated.

Well, okay, it does, but not in a bad way, and it even avoids later developed tropes such as the needlessly obstructive superior officer not allowing something just to inject a bit of human drama into it. Is it essential viewing in space year 2021? While the continued endurance of Godzilla makes viewing the original a worthwhile historical exercise, the Western arm of creature features has long been dead, excepting King Kong of course. Still, it’s nice to see what, arguable, launched a thousand imitators and popularised and normalised the subgenre so much that it eventually burned out. It’s an easy, breezy watch that doesn’t outstay its welcome. Go for it.

Outro

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply